In President Donald Trump’s vision, the United States reached its pinnacle during the 1890s, a time when fashion included top hats and shirtwaists, and diseases like typhoid fever were deadlier to soldiers than combat. Often referred to as the Gilded Age, this era saw swift population growth and a shift from an agricultural economy to a vast industrial system. While poverty was widespread, the wealthiest elite, such as John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan, wielded significant power over politicians, aiding in expanding their financial empires.

“We were richest from 1870 to 1913,” Trump claimed, shortly after assuming office. “That’s when we were a tariff country. And then they moved to an income tax concept. It’s fine. It’s OK. But it would have been much better otherwise.” Trump’s nostalgia for this era links to his fondness for tariffs and his admiration for William McKinley, the 25th U.S. president, a Republican who served from 1897 until his assassination in 1901.

Trump’s initial tariff policies have been inconsistent, with imposition followed by retracting many. Nonetheless, his commitment to 21st-century protectionism remains strong. There have been discussions that higher import tariffs could potentially substitute the federal income tax in the future.

Experts argue that Trump’s idealization of the Gilded Age overlooks the rampant corruption, social discord, and inequality of the time. They suggest he’s overestimating tariffs’ role in economic growth, which was more influenced by factors beyond raising taxes on imported goods. These policies from the Gilded Age are hardly relevant in today’s global economic landscape. “No one except the ultra-rich wanted to live in the Gilded Age economy,” said Richard White, a Stanford University history professor emeritus.

Trump believes that high tariffs and low interest rates, like those post-Civil War, could quickly pay down today’s federal debt, bolster government funds, support domestic manufacturers, and attract foreign businesses to the U.S. “I am a Tariff Man,” he pronounced in a 2018 online message. During his re-election campaign, he claimed, “We were a wealthy country in McKinley’s time, and we will do that now.” Tariffs, he said, represent “a very powerful weapon” often ignored by politicians due to dishonesty, ignorance, or other corrupt means.

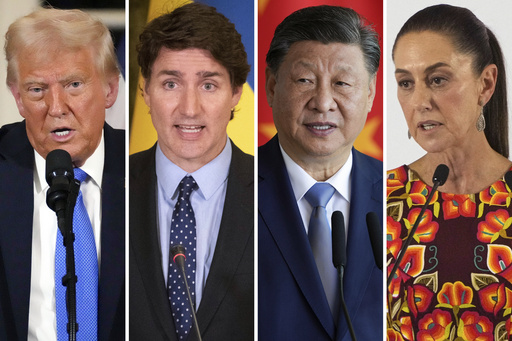

The White House has accelerated tariffs on Chinese imports and foreign aluminum and steel, with promises of further import levies on the European Union, foreign cars, microchips, and pharmaceuticals. Tariffs on Canada and Mexico were also raised but later postponed.

Economics professor Douglas Irwin critiques Trump’s use of tariffs by referencing the 1890s, calling it flawed. “The late 19th century saw rapid growth,” he observed, “but saying tariffs caused it is a stretch.” The most accurate historical narrative points to overall fiscal surpluses, not individual tariff policies, as the growth catalyst.

Was America truly at its wealthiest from 1870 to 1913? The Gilded Age highlighted incredible wealth for a few, while masking poverty for many others. The term stems from an 1873 satire by Mark Twain that mocked the greed and corruption of politicians. Influential figures like Rockefeller, Morgan, Vanderbilt, and Carnegie vastly changed American business landscapes, creating perceptions of wealth during a period of significant inequality.

The U.S. economy surged from 1870 to 1913, buoyed by major increases in industrial production. Yet, it faced economic fluctuations driven by immigrant labor changes and land grabs from Native Americans during westward expansion. Though average wages climbed, so did inequality, and horrific working conditions spurred the labor movement and progressive antitrust efforts.

White emphasizes the era was tumultuous, describing it as the height of political and labor turmoil. Despite growth, living standards fell, including life expectancy and health indicators.

Transitioning to tariffs potentially replacing federal income tax is not straightforward. The federal income tax emerged with the 16th Amendment in 1913, marking an end to the era Trump idealizes as the country’s wealthiest. Such a move would require Congressional action and could disrupt federal budgeting, as tariffs generate only a fraction of federal revenue compared to income tax.

On the topic of tariffs as government revenue, historical tariffs once formed half of federal revenue, but now it’s less than 2%. Even Trump’s own administration acknowledges that an IRS replacement focused on collecting foreign trade-related revenue won’t mimic income tax contributions.

Trump’s reverence for McKinley stems partly from the latter’s economic policies and business acumen. McKinley, another tariff advocate, enforced these dominant policies during an era void of income tax, central for federal coffers then. However, Trump’s use of tariffs diverges from McKinley’s methods, often deploying them as leverage over geopolitical disputes, not solely economic concerns.

McKinley, the so-called “Napoleon of Protectionism,” enacted the 1890 Tariff Act, which infamously increased tariffs to unprecedented levels. Although initially claiming to boost economic health, these policies led to economic inflation and political backlash, decimating Republican ranks and eventually returning McKinley to prominence in different political roles.

Today’s business magnates also seek Trump’s favor, as seen in high-profile meetings with industry leaders at Mar-a-Lago. Similar to McKinley’s financial backers, major technological firms and influential industrialists have shown interest in aligning with Trump’s agenda, hoping for potential regulatory relaxations.

Despite Trump’s inclination to echo McKinley-era tariff ideals, modern-day global trade complexity starkly contrasts with that era. Shipping logistics, multinational supply chains, and digital communications all stretch beyond tariff solutions, evidenced by post-pandemic supply chain challenges sparking recent inflation.

Interestingly, Trump and McKinley diverge notably on expansionism and trade reciprocity. While Trump considers bold territorial expansions, McKinley balanced territorial acquisitions with caution toward foreign markets. As reevaluation of tariffs became McKinley’s late-in-life pursuit, promoting reciprocal trade agreements, Trump’s recent initiatives will ultimately determine how aligned they truly are.

Tragically, McKinley was assassinated shortly after signaling this shift, while Trump continues to envisage new tariff policies. Yet the divergence in their eras’ complexities highlights the challenges of reviving past economic ideologies in the face of modern global challenges.