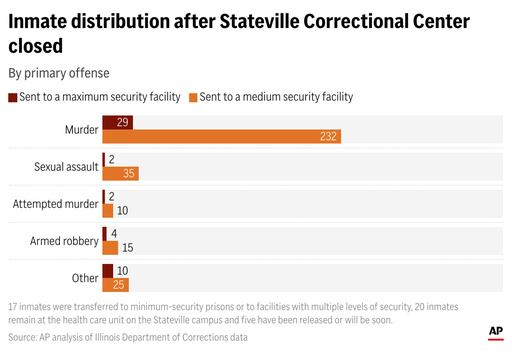

In the wake of the summer closure of the aging Stateville prison in Illinois, around 400 inmates were transferred, including 278 convicted of murder and an additional 100 serving sentences for other violent crimes. However, a significant majority of these individuals were not sent to high-security maximum-security facilities, which are intended for the most dangerous and problematic offenders. Instead, they were moved to mid-level medium-security institutions, as indicated by an analysis of data from the Illinois Department of Corrections.

Prison staff believe the decisions regarding where to place these transferred inmates were primarily influenced by the available bed space and the presence of adequately trained personnel in an overstretched system. Naomi Puzzello, a spokesperson for the corrections department, contended that all transferred inmates were suitably classified and admitted that there were numerous vacant spots in maximum-security facilities. However, she denied that the staffing shortage played a role in the placement decisions.

Despite Puzzello’s reassurances, meeting minutes obtained by the analysis, from a gathering that took place nearly a year before Stateville’s closure, showed that administrators were cautioning staff against reclassifying troublemakers to higher-risk levels due to a shortage of maximum-security beds. Furthermore, it was highlighted that over half of the inmates transferred violated existing guidelines that require individuals serving sentences of 30 years or more to be housed in maximum-security environments.

Stateville prison, which began operations in 1925, was recommended for closure after Governor JB Pritzker allocated $900 million for its replacement alongside the faciliities like Logan Correctional Center, which has similarly deteriorated. The plan took a turn for urgency when a federal judge ruled that Stateville was uninhabitable and demanded its closure by September 30.

The staffing crises in correctional facilities are a nationwide concern. The state of Wisconsin, for instance, has faced a worrying rise in inmate fatalities attributed to unfilled positions. A critical report from the Justice Department last fall pointed out severe staffing inadequacies in Georgia’s correctional facilities, noting the resulting spike in violence and abuse. Nationally, the number of state-employed corrections officers plummeted from 237,000 in 2012 to just 182,000 by 2023.

Illinois Department of Corrections is currently operating with a shortage of 396 frontline security officers compared to budgeted figures. The current numbers reveal that the overall contingent is down by more than 2,800 officers, which significantly impacts operational capacity.

Analysis derived from publicly available records indicated that 406 inmates were identified from Stateville in August 2024, tracing their movements to their new prisons while noting the corresponding security levels. While the state acknowledged 1,750 vacant beds in maximum-security facilities, most of these openings are in cells designed for two, while the majority of transferred inmates are accommodated in single-occupancy cells. This detail was viewed by Puzzello as a non-issue regarding staffing levels.

Concerns amongst employees persist, with some arguing that potentially dangerous inmates have been improperly placed in less secure environments, which could endanger both inmates and staff. An example cited involved a former Stateville inmate who attacked a prison educator, necessitating facial reconstruction surgery following a move to Sheridan Correctional Center.

Incidents such as suspected homicides among inmates have occurred since mid-2024, but the state has declined requests to release information on these instances. This refusal has led to appeals for transparency.

Concerns related to maximum-security bed shortages seem to have been prevalent even prior to the closure of Stateville. Documentation from a December 2023 management meeting at the Dixon Correctional Center showed that staff members were being advised to exercise caution before elevating an inmate’s risk classification due to limited bed availability in maximum-security units.

Puzzello reaffirmed that transfers from Stateville did not involve any downgrading of security levels. She explained that placements were determined by various factors, including inmate backgrounds, rehabilitation needs, and staffing levels at the receiving facilities. This method was said to ensure that each inmate’s classification matched their specific risks and requirements, thus maintaining a secure environment.

Existing guidelines state that offenders with sentences exceeding 30 years should be placed in maximum-security settings, while those with sentences between 10 and 30 years belong in mid-level facilities. Alarmingly, of the ex-Stateville inmates, 64% of those serving 30 years or more have been relocated to medium-security institutions.

Prison counselors involved in the evaluation process communicated reservations about the management’s predetermined decisions on inmate placements. Union representatives have raised alarms about ongoing instances where the recommendations of on-site facility employees, responsible for assessing and placing inmates, were disregarded by higher management.