In Atlanta, Allen Hall described the poignant moment when he boarded a bus alongside over 20 former residents of a homeless encampment. It was at this very location where a friend of his tragically lost his life after being struck by a bulldozer in the early part of the year. Though officials believed they had arranged housing for all known residents of the encampment, located on Old Wheat Street, Hall and seven others ended up staying temporarily in a hotel through the generosity of advocates.

Reflecting on the summer when friends began to settle into apartments after years spent on the streets, Hall noted, “It was like something was changing for us, for real.” With plans underway to host eight World Cup games the following summer, Atlanta officials and homeless service agencies are striving to significantly reduce the number of people experiencing homelessness before the influx of visitors. Their ambitious goal is to have about 400 individuals currently residing on the downtown streets safely housed by the end of the year.

However, obstacles persist, including lengthy waitlists for supportive living options funded by the city that often necessitate documents unattainable for many in Hall’s situation. These individuals have created communities downtown where they have access to social services, making it easy to miscalculate the population in encampments.

The heartbreaking death of Cornelius Taylor in January acted as a catalyst, rallying advocates into action. Tensions mounted as the city attempted to clear the Old Wheat Street encampment in preparation for Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebrations at the nearby Ebenezer Baptist Church. Once heightened concerns were raised, the city paused the encampment clearing process, which resumed this month amidst community unease.

Despite spending over three decades on the streets, Hall rejected a shelter space offered to him, citing general dissatisfaction with the conditions and strict rules of shelters. Originally, housing was proposed for 14 individuals counted at the encampment, but after consulting with residents and advocates who claimed the number was closer to twice that, additional housing efforts were made. Hall, who had resided in the encampment known as “Backstreet” for five years, was not initially listed.

Cathryn Vassell, CEO of Partners for HOME, explained, “Whether or not these were residents at one time, we rallied the requisite amount of housing that we could for the individuals that were known to us.” She added that more names were introduced at the last moment, prompting them to urgently find resources for everyone.

By making numerous visits to the encampment at different hours, case workers developed a list and a rapport with the residents. According to Vassell, seven more people have since been housed, predominantly at Welcome House, a supportive housing community. The city reported that the Justice for Cornelius Taylor Coalition had paid for a place to stay for eight individuals who, including Hall, declined shelter offers. Most of these individuals lacked the necessary documentation for Welcome House.

Advocates are urging swifter action, arguing that those who have received housing still lack adequate resources, which frustrates them. Tim Franzen, from the Justice for Cornelius Taylor Coalition, criticized the city’s approach, asking, “They say they’re gonna do good things, but we can’t take care of these eight people?” Observing months have passed since preparations began, he questioned the absence of a clear plan.

Shun Palmour, who moved to the encampment with his family after losing his job, has been placed by the city in a Motel 6. Complaining about being locked out of their room and motel management attempting to evict them, Palmour remarked, “Nobody comes out to make sure we’re eating.” Although they have been assigned a case manager from a local nonprofit, the family’s future remains uncertain.

Expressing gratitude for the assistance, Palmour voiced concern about the possibility of returning to homelessness, wondering, “Are we gonna end back up homeless or back on the street after this or what?” A city spokesperson has reassured that provisions are being made for meals, with efforts ongoing to secure permanent housing.

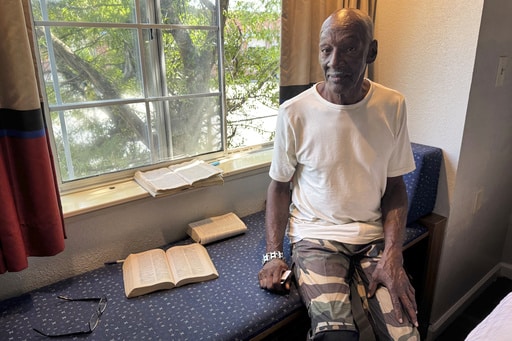

Now residing in another temporary location, Hall treasures a bracelet once given to him by Taylor. His time at the hotel was characterized by moments cherished for their simplicity—like enjoying coffee and relaxing in the comfort of a personal space, something he previously lacked. “It’s the normal things that people get to do,” Hall reflected, appreciating the ordinary yet invaluable experiences that many enjoy daily.