NEW YORK — Researchers have successfully dated the skeleton of an ancient child, a discovery that initially captivated scientists due to its blend of human and Neanderthal traits.

The remains, unearthed 27 years ago in Lagar Velho, a rock shelter in central Portugal, unveiled a nearly complete skeleton stained in red. Experts believe the child may have been wrapped in a painted animal hide as part of their burial.

Upon its discovery, the child’s anatomy displayed features resembling those of both humans and Neanderthals—namely, body proportions and jawbone structure. It was proposed that this child might be a product of the intermixing between human and Neanderthal populations—a concept once viewed as unconventional but now supported by genetic advancements. Modern humans continue to carry Neanderthal DNA, reinforcing this theory.

Determining the exact timeframe when this child lived, however, posed a challenge. Plant roots had invaded the bones, and contamination required scientists to abandon traditional carbon dating methods for determining its age. Instead, they focused on dating the charcoal and animal bones surrounding the skeleton, estimating it to be between 27,700 and 29,700 years old.

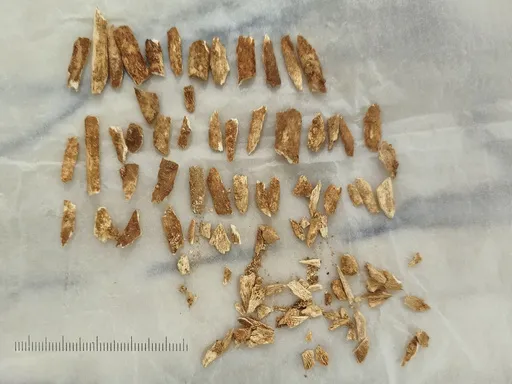

With technological progress, researchers have published findings in the journal Science Advances, where they applied a novel dating method based on measuring a protein predominantly found in human bones. This analysis, conducted on a fragment of a crushed arm, confirmed the initial dating estimates: the child lived between 27,700 and 28,600 years ago.

“Being able to successfully date the child felt like giving them back a tiny piece of their story, which is a huge privilege,” expressed Bethan Linscott, a contributing scientist to the study now affiliated with the University of Miami, through email correspondence.

She reflected on the initial discovery, noting it as more than just an ancient skeleton—it was the resting place of a young child. This connection left Linscott pondering who cherished the child, what moments brought them joy, and what their life encompassed during their brief four-year existence.

Paul Pettitt, an archaeologist at Durham University in England not involved in this research, commented via email that the study exhibits how evolving dating strategies are advancing scientists’ understanding of history.

Understanding our ancestral origins remains vital, stated study author João Zilhão from the University of Lisbon, akin to preserving the portraits of our parents and grandparents. “It’s a way of remembering,” he stated.