In Georgia, a recent legislative push aims to streamline the process for individuals facing the death penalty to demonstrate intellectual disability, potentially sparing them from execution. This move follows the execution of Willie James Pye, a man whose low IQ, as highlighted by his legal team, suggested intellectual impairment. This troubling event resonated with Representative Bill Werkheiser, a Republican from Glennville, who had previously introduced a bill proposing a simpler path to prove intellectual disability in death penalty cases. Although Werkheiser’s initial bill stalled in committee, a new version of the legislation has gained significant traction, receiving unanimous approval in the House and now awaiting Senate consideration.

Georgia pioneered legal protections against executing intellectually disabled individuals in 1988, a stance subsequently echoed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2002. However, the Supreme Court permitted states to set their own criteria for determining intellectual disability. Georgia’s stringent requirement—that one must prove the disability beyond a reasonable doubt—stands alone in its rigor among the states. Previous legislative efforts have considered revising this standard. The current bill proposes granting defendants the opportunity to present evidence of intellectual disability at a mandatory pretrial hearing, contingent upon the agreement of prosecutors. If found guilty, the accused could then reintroduce evidence of intellectual disability post-trial, potentially earning a life sentence instead of execution if the jury concurs.

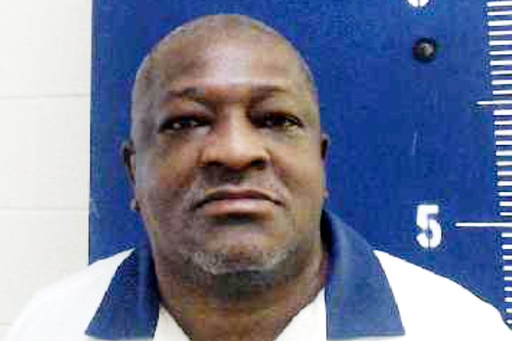

“I believe it is incumbent upon the state to protect those who cannot protect themselves,” Werkheiser emphasized. Pye’s conviction stemmed from the 1993 abduction, rape, and murder of Alicia Lynn Yarbrough. Pye’s defense argued he suffered from intellectual and brain impairment, a defense echoed in the 2015 execution case of Warren Lee Hill, where lawyers contended for his intellectual disability unsuccessfully. Similarly, Rodney Young’s 2021 death penalty case upheld by the Georgia Supreme Court highlighted the challenging threshold required to prove intellectual disability but included a judicial suggestion for legislative intervention to amend the standard.

Prosecutors, while open to lowering the reasonable doubt threshold, oppose procedural changes such as pretrial hearings. “The proposed bill cherry-picks from several different states,” commented T. Wright Barksdale III, district attorney for the Ocmulgee Judicial Circuit. Advocates for the bill stress the importance of pretrial assessments of intellectual disability, asserting that exposure to crime details during trials may bias jurors against objectively considering such evidence. This is a standard practice in most states, which separate the determination of intellectual disability from the trial of guilt.

“Changing only the standard of proof is insufficient for ensuring that Georgia does not continue to execute people with valid claims of intellectual disability,” declared Mazie Lynn Guertin, executive director of the Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. Barksdale III rebuffed claims that Georgia executes intellectually disabled individuals, arguing the bill’s complexity undermines the death penalty’s application. “As this law is constructed… it would for all intents and purposes cripple us to a point that we would never have a real fair shot at ever obtaining a death penalty for anyone,” he said.

Barksdale suggested that if legislators wish to abolish the death penalty, they should directly pursue that aim—a notion lawmakers dismiss. Both Republican and Democratic lawmakers, during hearings, appeared skeptical that the proposed procedural modifications would overly complicate proceedings. They noted that death penalty cases are inherently protracted, involving numerous motions and pretrial hearings. “We have the death penalty in this state. I’m not going to debate it,” stated Rep. Esther Panitch, a Democrat and criminal defense attorney. “But if we’re going to mete out the ultimate punishment, it should only be for the worst of the worst, and those we have spent the time to make sure understand their culpability.”