WASHINGTON — The recent discussions on tariffs have reignited debates about their impact and significance in the global trade arena. Essentially, tariffs are taxes imposed on imported goods. In the U.S., these are typically calculated as a percentage of the purchase price paid by the importer to the foreign seller. The responsibility of collecting these tariffs falls on Customs and Border Protection agents operating at 328 entry ports nationwide.

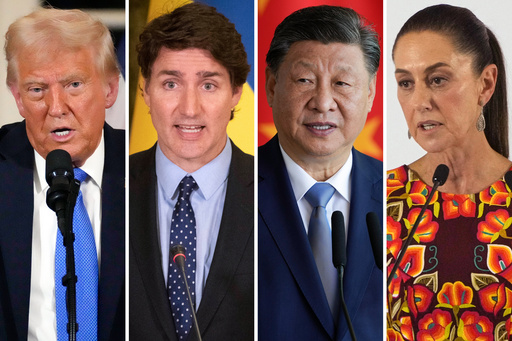

The United States applies different tariff rates to various products. For example, the rate is commonly 2.5% on passenger vehicles and 6% on items like golf shoes. However, for countries engaged in trade agreements with the U.S., these rates can be considerably reduced. An instance of this was seen prior to the U.S. enforcing 25% tariffs on Canadian and Mexican products; under President Donald Trump’s revised trade agreement with those nations, numerous goods were previously traded duty-free.

Economists generally express skepticism towards tariffs, viewing them as an inefficient method for government revenue generation. There’s often a misunderstanding about the real bearers of tariff costs. Although Trump has advocated for tariffs and claimed they’re financially burdensome for foreign nations, the reality is that American importers pay these taxes, which then contribute to the U.S. Treasury’s finances. American companies tend to offset these costs by raising prices for consumers, thus indirectly passing the tariff burden onto them.

Foreign economies might also feel the sting of tariffs. When their products become more expensive due to these taxes, it can hinder sales abroad. This can lead corporations overseas to reduce prices and juggle with profit margins to keep their hold on the U.S. market. Research by Yang Zhou, an economist from Shanghai’s Fudan University, revealed that Trump’s tariffs inflicted damage to the Chinese economy over thrice as heavily compared to the U.S.

Trump has opined that tariffs play a pivotal role in fostering factory job creation, narrowing the federal deficit, cutting food costs, and enabling the government to aid in childcare provision. During a rally in Flint, Michigan, he famously declared, “Tariffs are the greatest thing ever invented.” During his tenure, Trump pursued tariff implementation aggressively, targeting products from solar panels to Chinese goods entirely, earning himself the nickname “Tariff Man.”

The U.S. has gradually retreated from its post-World War II stance advocating for global free trade and minimized tariffs, partially as a reaction to domestic manufacturing job losses attributed to unregulated trade and China’s manufacturing boom. The primary purpose of tariffs is the protection of domestic industries by inflating the cost of imports. Historically, prior to national income tax establishment in 1913, tariffs significantly contributed to federal revenue. From 1790 to 1860, they accounted for a majority of the government’s income, as documented by Douglas Irwin, a trade policy historian from Dartmouth College.

In contemporary times, especially in the fiscal year ending September 30, the government amassed roughly $80 billion from tariffs, a figure dwarfed by the trillions generated through income and payroll taxes. Despite this, Trump shows favor towards a fiscal approach reminiscent of the 19th century. Occasionally, tariffs serve broader foreign policy aims, such as the 2019 instance when Trump leveraged the threat of tariffs to encourage Mexico to curb Central American migrant flows through its territory. In a rather unorthodox view, Trump also sees tariffs as a tool to avert war, suggesting in a North Carolina rally that threats of exorbitant tariffs might dissuade nations from military conflict.

Economists frequently criticize tariffs as ultimately counterproductive. They push up costs for import-dependent companies and consumers and are likely to spark retaliatory actions. For instance, the European Union responded to Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs with taxes on U.S. goods, ranging from bourbon to motorcycles. Similarly, China’s retaliation aimed at American soybeans and pork reflected attempts to wield political pressure against Trump’s rural base.

Findings from a study by economists at prestigious institutions such as MIT, the University of Zurich, Harvard, and the World Bank indicate that the tariffs enacted during Trump’s presidency fell short of revitalizing American employment. Jobs in sectors purportedly shielded by tariffs remained unchanged. Despite the 2018 tariffs on foreign steel, U.S. steel plant employment stagnated, maintaining a workforce of about 140,000 compared to the massive employment figures seen at companies like Walmart.

The negative impact from reciprocal tariffs, particularly affecting U.S. agriculture, was partly alleviated by extensive government aid. However, even as a trade strategy, Trump’s approach largely faltered; politically, however, it did find success. Support for Trump and Republican candidates grew in areas hit hardest by import tariffs, particularly the industrial Midwest and manufacturing-centric parts of the Southern U.S.