Measles, a rare occurrence in the United States, is causing increasing concern among Americans as cases escalate in rural West Texas. Recently, the outbreak led to the death of an unvaccinated child, with over 150 reported cases. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noted that the last confirmed measles-related death in the country occurred in 2015. The CDC tweeted that their team is actively working in Texas, following the state’s request for federal assistance to manage the outbreak.

The current measles situation extends beyond Texas. The state has recorded the most cases nationwide this year, with New Mexico reporting nine cases, although the local health department clarified that these are not linked to Texas. Further reports of measles cases have emerged from various states, including Alaska, California, Georgia, Kentucky, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island. The CDC classifies an outbreak as three or more related cases, and so far, three clusters have met the outbreak criteria in 2025. The U.S. cases often originate from someone contracting the disease abroad, spreading further in communities with low vaccination rates.

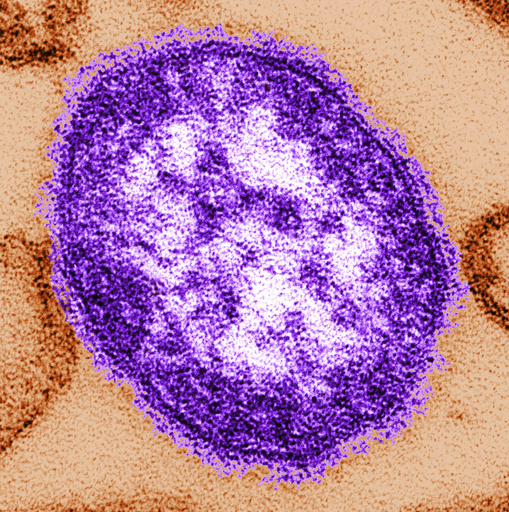

Measles is a highly contagious respiratory illness caused by a virus that spreads through the air when an infected individual breathes, sneezes, or coughs, predominantly affecting children. Scott Weaver, a director at the Global Virus Network, highlighted the virus’s contagious nature, noting one infected person can infect about 15 others. Initially attacking the respiratory tract, the virus can then invade the body, leading to symptoms like high fever, runny nose, cough, red itchy eyes, and a rash. This rash appears three to five days into the illness, starting as red spots on the face and spreading. The CDC warns that fevers may spike over 104°F during this stage.

While no specific treatment exists for measles, medical professionals focus on alleviation of symptoms and preventing complications. Once a person recovers from measles, they typically develop immunity. Despite its potential severity, measles is not frequently fatal. Common complications include ear infections and diarrhea, but the CDC reports that 1 in 5 affected unvaccinated Americans might require hospitalization. Pregnant women without immunity might face premature birth or low birth weight issues. Furthermore, about 1 in 20 children with measles can develop pneumonia, and 1 in 1,000 can endure brain inflammation, possibly resulting in convulsions, deafness, or mental disabilities. Weaver, from the University of Texas Medical Branch, emphasized its lethality in less than 1% of cases, mainly in children, usually due to pneumonia-related complications.

Vaccination remains the most effective preventive measure against measles. Health officials advise children to get the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, with the first dose recommended between 12 and 15 months and the second between 4 and 6 years. Weaver recalls that before the development of vaccines in the 1960s, measles was nearly universal. The introduction of the vaccine drastically reduced its prevalence, marking a significant medical advancement. Decades of data underscore the vaccine’s safety and efficacy, and Weaver stresses that outbreaks can be prevented by maintaining high vaccination rates. Due to the decline in vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states now fall below the 95% threshold required for community immunity.

ADults may not need additional MMR doses now, according to the CDC. Adults considered to have “presumptive evidence of immunity”—including those with prior vaccination documentation, previous infection, or born before 1957—generally don’t need the vaccine. However, those vaccinated with a “killed” virus before 1968 are advised to get revaccinated. Weaver suggests that individuals at high risk for infection who had prior vaccinations might consider boosters, especially in outbreak-prone areas or if they have complications that heighten vulnerability to respiratory diseases. He reassures that those who received the standard two vaccination doses in childhood are generally safe and highlights that widespread standard vaccination would prevent such crises.

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation support the Associated Press Health and Science Department, which remains solely responsible for its content.