BUDAPEST, Hungary — As the world marks the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, a notorious Nazi death camp, Tamás Léderer reflects on the profound impact the Holocaust had on Hungarian Jews, a tragedy that claimed nearly half a million lives. Having been born in Budapest in 1938, Léderer is one of the few from his community who managed to survive, thanks to his family’s efforts to keep him hidden from the Nazis. They concealed his Jewish identity by removing the mandatory yellow star from his clothing, allowing him to evade deportation during this dark period.

On January 27, 2025, which coincides with International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Léderer, now 87 years old, expresses his concerns about the ongoing threat of hatred and violence towards Jews and minority groups. He feels a deep responsibility to remember and honor the approximately 565,000 Hungarian Jews who perished in the Holocaust, acknowledging that the potential for history to repeat itself looms large in his mind. “I must not forget,” he stated, emphasizing the weight of such memories. “In my subconscious, I can never get over the possibility that a six-pointed star could be placed on my gate again at any moment. It is always in my mind.”

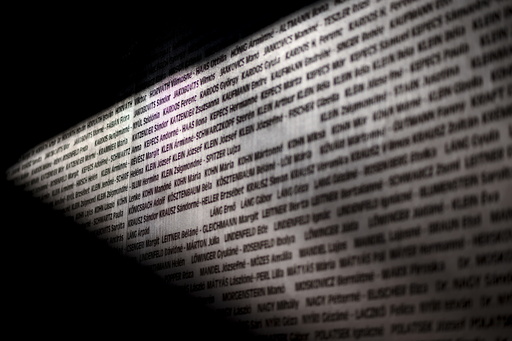

The Holocaust saw the systematic murder of around 6 million Jews across Europe, with nearly 10% of this number coming from Hungarian territories alone. Within Auschwitz-Birkenau itself, about 1.1 million people lost their lives, with around 435,000 of them being Hungarian Jews, making up the largest group represented there.

Tamás Ver?, a respected rabbi in Budapest, also carries family scars from this era. His grandmother, a survivor of Auschwitz, often expressed gratitude for his decision to become a rabbi, believing it served to ensure that the genocide would not be forgotten. “We carry in our genes what our grandparents’ or our parents’ generation went through,” he noted. He believes that maintaining a living memory of the past is crucial for current and future generations of Jews, enabling them to embrace their heritage fully.

When the Second World War erupted, Hungary, which was a monarchy at that time, allied itself with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy as part of the Axis powers. Its leader, Regent Miklós Horthy, pushed for a restoration of territories lost after World War I and introduced anti-Jewish legislation as early as 1920. Horthy initially resisted Nazi pressures to deport Hungary’s substantial Jewish population, but as fears grew of his potential defection to the Allies, Hitler invaded Hungary in March 1944, prompting a wave of mass deportations.

From March to May of 1944, approximately 435,000 Jews, primarily from rural communities, were sent to Auschwitz, where most met grim fates upon arrival. As the war neared its conclusion, additional atrocities were committed by Hungary’s fascist Arrow Cross party, whose members executed Jews en masse by the banks of the Danube River in Budapest.

On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Ver? and several others assembled at the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest. Ver? led the group, including some Holocaust survivors, in a solemn prayer. The center’s director, Dr. András Zima, poignantly referred to Auschwitz as “the largest Hungarian mass grave.”

For Ver?, keeping the Holocaust’s memory alive serves as a commitment to ensuring such inhumanity is never tolerated again. However, Léderer, who continues to express his artistic vision from his home near Budapest, feels that Hungarian society continues to grapple with its dark past and refuses to confront the nation’s complicity with the Nazis.

“It’s just a matter of time before we get to a moment where people think the time has come to hate someone again,” Léderer warned, underscoring the need for continued vigilance against the rising tide of intolerance.