TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Hidden within Florida’s pristine golf courses and expansive suburban neighborhoods are remnants of its history tied to slavery: forgotten cemeteries of the enslaved, enduring Confederate monuments, and historic plantations that now exist as modern communities. However, many students in Florida are not receiving a comprehensive education about Black history in their classrooms.

In a quaint wooden bungalow situated in Delray Beach, Charlene Farrington and her team meet with groups of teenagers on Saturday mornings to enlighten them with information she fears public schools might overlook. Their discussions cover a range of topics including South Florida’s Caribbean heritage, the grim narrative surrounding lynchings in the state, the lasting impact of segregation, and how grassroots activism fueled the Civil Rights Movement to challenge long-standing injustices. “Understanding past events is crucial to determine the future,” she conveyed to her pupils as they attentively observed historic photographs adorning the walls.

Students are dedicating their Saturday mornings to delve into African American history at the Spady Cultural Heritage Museum, as well as other similar initiatives across Florida, often backed by Black churches pivotal in shaping the cultural and political identity of their communities. Since the establishment of a Black history toolkit by Faith in Florida last year, over 400 churches have committed to imparting these lessons, the advocacy group reports.

Though Florida has mandated the teaching of African American history in public schools for the past three decades, many families express skepticism regarding the educational system’s capability to address the subject adequately. According to state assessments, only twelve out of Florida’s school districts have showcased excellence in teaching Black history by evidencing the integration of relevant content throughout the academic year and securing involvement from school boards and local partners.

Officials from school districts statewide maintain that they adhere to the state requirement to educate students about slavery, abolition, and the critical contributions of African Americans to society. Nonetheless, students and parents frequently voice concerns that the curriculum tends to focus on well-known figures, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, without offering a broader perspective beyond the confines of February’s Black History Month.

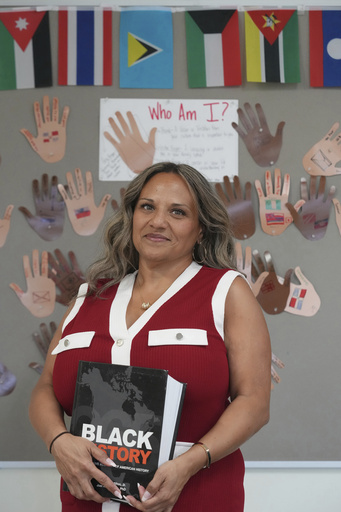

When Sulaya Williams first sought a well-rounded education in Black history for her eldest child, she found the available resources lacking in her area. Consequently, in 2016 she established an organization aimed at providing Black history education through community platforms. “Our goal is to ensure our children learn their history so they can pass it down,” Williams stated. She now conducts Saturday classes at a public library in Fort Lauderdale, where her 12-year-old daughter, Addah Gordon, encourages her classmates to join.

“It feels like I’m genuinely connecting with my culture and discovering the contributions of my ancestors,” Addah remarked. “Most people are unaware of what they accomplished.”

The mandate for Black history education came during a phase of reflection within the state. In 1994, legislators unanimously passed a law requiring African American history instruction at a time when awareness about Florida’s past was increasing. An official report had recently revealed the 1923 attack on the predominately Black town of Rosewood, where a white mob destroyed homes and drove out residents. The state’s decision to offer compensation to the survivors and their descendants was celebrated as a landmark for reparations.

“Florida exhibited a moment of clarity many years ago, but that awareness faded,” remarked Marvin Dunn, a renowned author on Black Floridians. Decades later, the delivery of African American history lessons remains inconsistent across schools, creating frustration among advocates, especially with Governor Ron DeSantis’ administration, which has sought to restrict discussions around race and history in public education. Under DeSantis, a law was enacted in 2022 that limits race-focused dialogues and forbids teaching that could instill a sense of guilt among individuals of certain ethnicities regarding past injustices.

Additionally, the DeSantis administration blocked the introduction of a new Advanced Placement course covering African American Studies, claiming it contradicted state law and contained historical inaccuracies. Currently, no public schools in Florida seem to offer this course, as confirmed by the College Board overseeing AP programs.

An advocate for advancing African diaspora history, Tameka Bradley Hobbs, emphasized that relying solely on schools for such education could be problematic, advocating instead for a proactive approach to preserving ancestral history and culture. “There’s an urgent need to focus on self-reliance and determining how we share our heritage,” she noted.

Data reveals that only 30 of Florida’s 67 traditional school districts provided at least one standalone African American history course last year, illustrating a gap in educational offerings despite the mandate not requiring dedicated courses. Larger urban districts more frequently offer such classes compared to their smaller rural counterparts. Even teachers in districts with programs dedicated to Black history report feeling uneasy about potential repercussions from state regulations, creating further obstacles in delivering comprehensive education.

Frustrated by these limitations, Renee O’Connor took a sabbatical from her position teaching Black history at Miami Norland Senior High School before returning, now also aiding community organizations in developing independent Black history programs. “It’s unfortunate that not all students can access an African American history course, but we must adapt if that isn’t available within formal education,” O’Connor concluded.