Marie Dageville and her husband, Benoit Dageville, experienced a dramatic shift in their lives when Benoit’s cloud data company, Snowflake, went public in September 2020, catapulting them into billionaire status. Following this transformative event, Marie, who previously worked as a hospice nurse, dedicated herself to figuring out how to effectively give away their newfound wealth.

“We need to redistribute what we have that is too much,” she stated during a conversation from her home located in Silicon Valley.

While many individuals often express trepidation about parting with large sums, Marie believes in taking immediate action. Her approach encourages others to start their philanthropic journeys without delay.

The discussion around philanthropy among America’s wealthiest individuals dates back to at least 1889, with Andrew Carnegie’s essay, “The Gospel of Wealth,” advocating that the affluent ought to spend their fortunes during their lifetimes as a way to counteract increasing inequality. The landscape of charitable giving has evolved significantly since then, with a plethora of advisors, educational programs, and donation frameworks emerging to assist wealthy individuals in their charitable endeavors. This evolution has been partly driven by the Giving Pledge, launched in 2010 by Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and Melinda French Gates, which encourages billionaires to promise to donate at least half of their wealth either while living or through their estates. To date, 244 individuals have committed to this initiative.

However, several barriers exist that prevent the ultra-wealthy from donating their funds more generously and promptly. These obstacles include risk assessment, logistics, and emotional factors involved in philanthropy.

Philanthropic advisors highlight that many of these limitations are structural, revolving around operational complexities and finding proper channels for their contributions. Some barriers originate from personal emotions, such as family dynamics or perceptions among peers. Piyush Tantia, an innovation officer at ideas42, remarked, “It’s like a massive, perfect storm of behavioral barriers,” pointing to recent research funded by the Gates Foundation that investigates why some affluent donors hesitate.

He explained that unlike ordinary donors who may respond to requests from family or friends, significant donors tend to spend more time deliberating over their contributions. “We might think, ‘It’s a billionaire. Who cares about a hundred grand? They make that back in the next 15 minutes,’” he noted. “But it doesn’t feel like that.”

Tantia recommends a framework in which donors treat their charitable contributions like an investment portfolio, with varying risk levels and strategies working together. This perspective shifts the focus from the success of individual donations to the overall, cumulative impact of their philanthropy.

Marie Dageville acknowledges the value of engaging with other philanthropists, particularly those who have committed to the Giving Pledge. She recalled valuable advice from peers that emphasized making flexible operating grants—essentially allowing organizations to prioritize spending as they see fit. She trusts nonprofits’ intimate knowledge of their communities and believes there’s no need for concern about potential misuse of funds.

“If you are in the position where you are at now — able to redistribute this fortune — either you took risks or someone took risks on you,” she reflected, urging others to adopt a similar mindset in their philanthropic actions.

Encouragement and knowledge-sharing among donors can also facilitate giving, according to philanthropic advisors. The University of Pennsylvania’s Center for High Impact Philanthropy has created programs that bring wealthy donors, their advisors, and foundation leaders together for collaborative learning experiences. Kat Rosqueta, the center’s executive director, emphasized how figures like MacKenzie Scott, the author and former wife of Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, have shown that it is possible to act swiftly in philanthropy.

“Do all the ultra-high-net-worth funders have to go slower than MacKenzie Scott? No,” she asserted. Yet she acknowledged that many donors struggle to understand how their contributions can make a difference in the broader context, given that philanthropic funding represents a fraction of government expenditures and corporate efforts.

Cara Bradley, deputy director of philanthropic partnerships at the Gates Foundation, noted that the scrutiny on billionaire philanthropy places significant pressure on donors to maximize their impact. “They’ve signed a pledge genuinely committed to trying to give away this tremendous amount of wealth. And then, people can get stuck because life gets busy. This is hard. Philanthropy is a real endeavor,” she explained.

Additionally, conducting empirical research into billionaire giving poses challenges, as observed by Deborah Small, a marketing professor at Yale School of Management. She commented on the existing societal norm that favors anonymity in charitable contributions, which is often perceived as more virtuous despite its drawbacks.

“It would be better for causes, and for philanthropy as a whole, if everybody was open about it because that would create the social norm that this is an expectation in society,” she suggested.

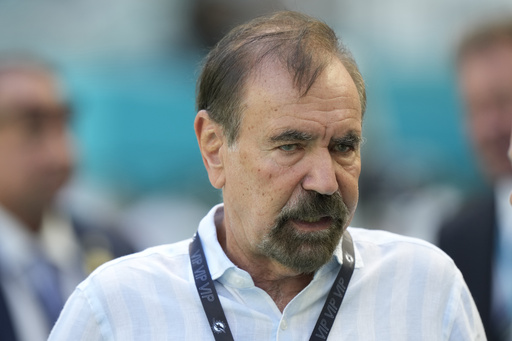

Jorge Pérez, the founder and CEO of Related Group, along with his wife Darlene, joined the Giving Pledge in 2012 and actively discusses philanthropic strategies with his peers.

“I think people have stopped taking my calls,” he joked, pointing out that he has involved his adult children in their philanthropic efforts, primarily through The Miami Foundation. They opted to leverage the foundation’s expertise to facilitate a more effective evaluation of potential grantees.

Even prior to their commitment to the Giving Pledge, the Pérez family consistently contributed to Miami’s arts and educational scholarships. Notably, in 2011, they donated an impressive art collection along with cash, totaling $40 million, to a local art museum, which subsequently adopted their name.

Pérez expressed his philanthropic philosophy, stating that he believes very unequal societies are unsustainable and that he aims to establish a meaningful legacy. “I keep on selling the idea that you’re giving because of very selfish reasons,” he remarked. “One is it makes you feel good. But two, particularly in the city or the state or the country that you’re going to live in, in the long run, this is going to make a huge difference in making our society fairer, better and more progressive and probably lead to greater economic wealth.”