NEW YORK — The story of the Meatpacking District in Manhattan takes a poignant turn as the district’s last remaining meat market prepares to close its doors. This area, once bustling with over 200 slaughterhouses and packing plants, has transformed drastically since John Jobbagy’s grandfather arrived from Budapest in 1900, marking the beginning of a long family history in the meatpacking trade.

Jobbagy, along with the other tenants of this final meat market, has reached an agreement with the city for relocation to facilitate the redevelopment of the space. This marks the conclusion of a decades-long evolution of a neighborhood that has shifted its identity from an industrial center to a hotspot for high-end boutiques and fashionable dining establishments.

Reflecting on the bygone days of his youth, the 68-year-old Jobbagy expressed nostalgia for a neighborhood that has been transformed beyond recognition. “The neighborhood I grew up in is just all memories,” he shared, recalling when the area was an industrious hub where meat was rapidly processed and sent out to markets.

In its prime, the Meatpacking District served as a vital junction for meat and poultry distribution, thanks to its strategic location near shipping and rail lines. However, with the growth of residential and recreational amenities like the High Line park, retired docks, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, the district bears little resemblance to its former self.

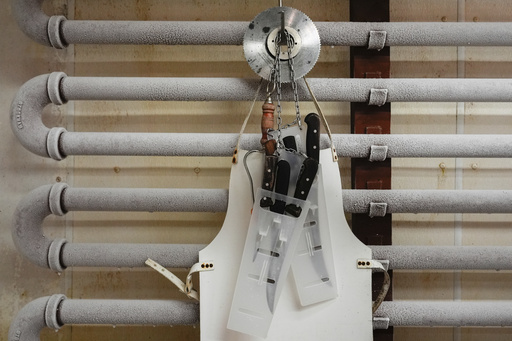

While certain new retailers still pay homage to the district’s meaty legacy, with signs from previous butcher establishments adorning their storefronts, the scent and atmosphere have undeniably shifted. Jobbagy remembers the pungent odors and the camaraderie among meatpackers who often kept whiskey tucked away for warmth during long hours spent in the chilly plants.

The evolution of the meatpacking industry can be traced back to technological advancements in refrigeration and packaging, which allowed operations to centralize in the Midwest. This led many local firms to shut down or relocate. As the 1970s rolled in, a new nightlife scene burgeoned, with bars and clubs emerging, blending the old and new as the neighborhood transitioned into a cultural hotspot.

For many, the breaking point was highlighted in popular culture with characters like Samantha from “Sex and The City,” who embraced the area’s transformation by 2000. The cultural shift continued, notably marked by the High Line’s opening in 2009, which revitalized the landscape and ushered in an era of luxury living amidst remnants of its industrial past.

Jobbagy reflects on this change with sadness, noting that his father, who passed away just prior to the High Line’s unveiling, would have found the transformation incredible. “If I told him that the elevated railroad was going to be turned into a public park, he never would have believed it,” he remarked.

Andrew Berman of Village Preservation acknowledged the district’s ever-evolving identity. “It wasn’t always a meatpacking district. It was a sort of wholesale produce district before that, and it was a shipping district before that,” he explained, highlighting the Meatpacking District’s layered history that has seen it transition through various functions over the years.

With no exact date for the final closure of the market, Jobbagy is poised to be the last meatpacker standing, as he continues to supply select high-end restaurants and retail establishments. He looks forward to retirement alongside his brother and dedicated employees, many of whom are immigrants who have aspirations beyond meatpacking.

As the cleaver is set to fall on Gansevoort Market, Jobbagy feels a sense of pride in his long-standing legacy within the community. “I’ll be here when this building closes, when everybody, you know, moves on to something else,” he stated. “And I’m glad I was part of it and I didn’t leave before.”