DILKON, Ariz. — Felix Ashley navigates the rugged terrain of the Navajo Nation in his red Toyota, leaving behind a cloud of dust as he makes his way to the water pump. This route also marks the path voters travel during presidential elections, navigating the same challenges faced in their day-to-day lives.

In this often-overlooked corner of the Navajo Nation, which is the largest Native American reservation in the United States, struggle is woven into the fabric of existence. Roughly a third of homes like Ashley’s lack access to running water, and soaring rates of unemployment and poverty have pushed many young Navajos—including Ashley’s own children—to seek their futures outside their ancestral land. The challenges of navigating the electoral process in Arizona have further complicated voting for the state’s 420,000 Native citizens.

“When people feel let down by their government, they lose interest in voting,” said the 70-year-old Ashley, who, alongside his family, offers rides to those hitchhiking to polling places on Election Day. Despite the trials, Native voters like him hold significant sway in determining outcomes in Arizona and some of the crucial swing states in upcoming elections. In 2020, Arizona elected a Democratic president for the first time in decades, with Joe Biden winning by a narrow margin of about 10,500 votes.

According to data analysis, Native American voter turnout surged, predominantly supporting the Democratic Party. Political candidates from both sides now vie for the attention of this critical electorate, realizing the importance of Native votes in a state where margins can be razor-thin. “Native voters have the power to influence the next presidential election,” stated Jacqueline De León, an attorney specializing in voting rights with the Native American Rights Fund. “It’s evident that the results in Arizona may hinge on just around 15,000 votes.”

Campaigns are making efforts to connect with Native communities more than ever. One Senate candidate trekked down to a hard-to-reach tribe, only accessible by helicopter or long hikes, while another joined a local parade in Tuba City to rally support. Brightly colored campaign signs featuring messages for candidates like Donald Trump and Kamala Harris are visible at local fairs, with radio advertisements playing frequently in remote areas where internet connectivity falters.

Yet Native voters pose a fundamental question to these candidates: What have you done for us? The feeling of being overlooked isn’t new for the 22 federally recognized tribes in Arizona, spanning from the rugged homes of the Hopi reservation to the isolated locations where Ashley collects water for his family.

Frustration has mounted among the residents, who feel let down by local tribal governments and distant politicians in Washington. Ashley, a lifelong Democrat, shared his own struggles—especially regarding the long distances required to access veteran healthcare services and the financial constraints imposed by skyrocketing inflation. “Promises of jobs and running water remain unfulfilled,” he lamented.

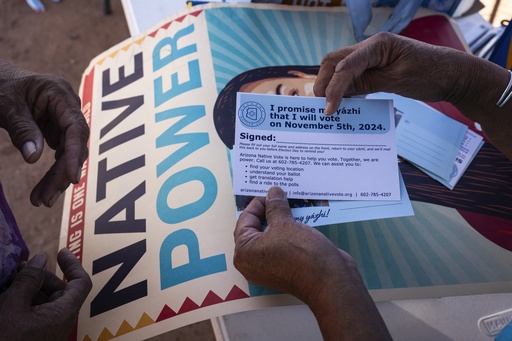

For many Native citizens in Arizona, the obstacles to voting are steep. Some must travel as far as 285 miles just to cast their ballots. Many residences on reservations lack the conventional addresses required for voter registration, leading committed volunteers to visit homes, assisting residents by pinpointing their locations on maps. Language barriers further complicate the process; organizers often provide language-specific information to older residents less familiar with English.

This logistical struggle is compounded by a troubling history of voter suppression against Native communities. Although Native Americans achieved U.S. citizenship a century ago, Arizona barred them from voting until 1948. Legislative efforts throughout the decades imposed various barriers, including literacy tests, as recently as 2022, when new laws aimed to tighten voter identification requirements. Though these measures were ultimately invalidated by the Supreme Court, many Native ballots were disregarded in prior elections. Consequently, rejection rates among Native voters remain disproportionately high. Consequences of these systemic issues foster a prevailing skepticism about government promises. “Thin margins in elections mean that excluding even a small community can drastically affect outcomes,” De León emphasized. “Many Native Americans still struggle to exercise their full rights as citizens because voting remains a challenging endeavor.” Traditionally, Democrats have enjoyed a stronghold on reservations, expanding their outreach among Native voters. High-profile campaign events—like Kamala Harris engaging with Native youth—and visits from President Biden have aimed to solidify this support. Democrats assert that the Republican Party has historically failed to prioritize Indigenous issues, as illustrated by statements made by opposing candidates to win over tribal voters. Conversely, Republicans are launching concerted initiatives to draw Native voters away from the Democrats. This includes establishing their first campaign offices on the Navajo Nation and actively participating in community events. The desire for shifts in voter allegiance echoes among many Native voices, who list inflation and economic issues as their foremost concerns, even while most remain aligned with Democratic ideals. Former Democrat, Francine Bradley-Arthur, expressed her shift towards supporting Trump due to feelings of discontent with the payoff from years of Democratic support—echoing sentiments across various minority groups nationally. Political dynamics remain tense ahead of the upcoming election, as candidates step out to connect with some of the most isolated communities. Democratic Senate candidate Ruben Gallego emphasized this point by taking significant strides to address the concerns of smaller tribes, focusing his campaign efforts on areas like the Havasupai reservation, which is marked by limited resources. Even as political candidates attempt to bridge the gap with voters concerned about essential issues like water rights, skepticism persists among tribal leaders like Dinolene Caska, who urges genuine support for Indigenous concerns over party loyalty. “If issues regarding Indigenous rights are not prioritized, we must evaluate who we support, regardless of political affiliation,” she remarked, alluding to her Democratic leanings. For individuals like Ashley, the upcoming election will center on the continuing fight for water rights and other pressing social needs, while others may explore new avenues in political support. Richard Begay, in contrast, taps into the Republican platform as a potential solution for economic growth, attributing his loyalty to gripping inflation and limited job offerings that have plagued the local community. He ardently hopes that a shift in leadership could herald new opportunities within the reservation. As discussions unfold regarding the electoral preferences of the Navajo and other Native voters, one sentiment resonates widely: the feeling of being used by the political system doesn’t discriminate between party lines.