Missouri’s chief prosecutor has faced a setback in his efforts to contest a judge’s ruling that vacated the murder conviction of a woman who spent an astonishing 43 years in prison for a crime her legal team contends was committed by a disgraced police officer.

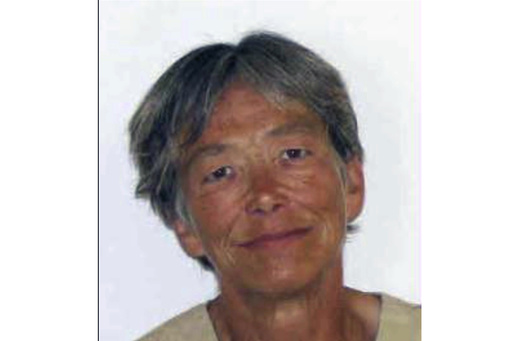

An appellate court ruled in favor of Sandra Hemme on Tuesday after she was released in July, while Attorney General Andrew Bailey pushed for the review of the decision to overturn her conviction.

Presiding Judge Cynthia Martin delivered a pointed and detailed 71-page decision that deemed some of the arguments from Bailey’s office as bordering on “absurd,” and instructed prosecutors to refile charges within ten days.

“It is time for this miscarriage of justice to end,” stated Hemme’s attorneys in a public comment.

According to the Innocence Project, Hemme was recognized as the longest wrongly incarcerated woman in the United States.

A spokesperson for Bailey did not provide an immediate response regarding the ruling.

Hemme was heavily medicated with antipsychotic drugs during her initial questioning related to the 1980 murder of 31-year-old Patricia Jeschke in St. Joseph. Sean O’Brien, one of Hemme’s lawyers, referred to the medication as a “chemical straightjacket” in a hearing last October, raising concerns about the validity of her eventual confession.

“It makes her compliant,” O’Brien explained. “It makes her subject to susceptibility.”

Further support for Hemme’s innocence included evidence that had been hidden, implicating Michael Holman, a former police officer who passed away in 2015. The evidence indicated that Holman’s truck was spotted near Jeschke’s residence, he attempted to use her credit card, and her earrings were located in his house.

The appellate court’s findings suggested strongly that law enforcement may have neglected investigations into Holman.

This conclusion was echoed in June, when Judge Ryan Horsman in Livingston County reverse Hemme’s conviction, determining that her defense team had provided “clear and convincing evidence” supporting her “actual innocence.”

Bailey, however, sought an appellate review of that ruling, contending that Horsman had overstepped his bounds and asserting that Hemme had not produced enough evidence for several of her claims.

A protracted legal struggle ensued to determine whether Hemme should remain imprisoned while awaiting the review. A circuit court, the appellate court, and even the Missouri Supreme Court all found in favor of her release, yet she continued to be detained as Bailey argued she had remaining time on old assault convictions.

Hemme was finally freed only after Judge Horsman threatened to hold the attorney general’s office in contempt.

During the latest hearing, Assistant Attorney General Andrew Clarke faced rigorous questioning, particularly concerning the implications of Holman, the discredited officer, being unable to be excluded as the source of a palm print found on a TV antenna cable near the victim’s body.

The FBI had requested clearer palm prints, but police failed to act on that request, and jurors were never made aware of this or other crucial evidence due to law enforcement’s lack of communication with prosecutors.

“The court,” Clarke remarked when asked about the importance of suppressed evidence, “has to consider what its value is at a future trial, what it would look like. And if it undermines confidence in the prior verdict.”

Clarke suggested that some of the evidence might not have reached the threshold for presentation in court—a point that was met with skepticism by the judges.

Bailey has a track record of opposing cases where convictions have been overturned. Earlier in July, a St. Louis circuit judge granted Christopher Dunn’s release from a murder conviction, which was based, in part, on the recanted testimonies of two children who later claimed they were coerced by law enforcement.

Bailey attempted to appeal this decision in a bid to re-incarcerate Dunn before he was ultimately set free.