Fifty years back, the Philadelphia prison system put an end to a controversial medical research initiative that had permitted a researcher from an Ivy League school to conduct experiments on inmates for an extended period, particularly targeting Black individuals. Today, both survivors of this program and their families are advocating for reparations.

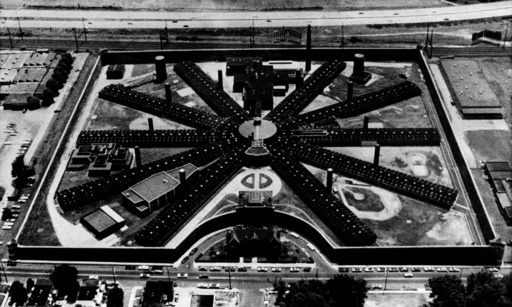

At Holmesburg Prison, thousands of inmates were subjected to a range of distressing medical experiments, including painful skin tests, surgeries without anesthesia, exposure to dangerous radiation, and the administration of mind-altering drugs. These tests were part of research ranging from everyday products like hair dye and detergent to studies involving chemical warfare agents and dioxins. In return for participating, inmates would often earn a mere dollar a day, which they could spend on commissary goods or use towards bail.

Herbert Rice, a former city worker from Philadelphia, explained how he and others were exploited, stating, “We were fertile ground for them people.” He has suffered from lasting psychiatric issues since taking an unidentified drug at Holmesburg in the late 1960s that induced hallucinations. He compared the situation to “dangling a carrot in front of a rabbit.”

Recently, the city and the University of Pennsylvania have issued public apologies regarding the program. However, legal efforts aimed at securing justice for the affected individuals have largely failed, aside from a few minor settlements. On Wednesday, families affected by this history are planned to gather at a Penn law school event to pursue reparations from the university and pharmaceutical companies they claim benefited from the unethical research conducted during the Cold War era.

A spokesperson for the University of Pennsylvania declined to comment on the current call for reparations.

The research was primarily conducted by Albert M. Kligman, a dermatologist from the University of Pennsylvania who had connections to the Army, CIA, and the pharmaceutical sector, as detailed by writer Allen Hornblum, who oversaw an adult literacy program at Holmesburg in the 1970s and witnessed the consequences of these tests firsthand.

The phenomenon of medical testing within prisons was widespread during the 1960s, encompassing various studies such as radiation tests on inmates in Washington and Oregon, cancer studies in Ohio, and flash burn experiments in Virginia, as Hornblum noted.

Additionally, human experimentation targeted children in institutional settings, hospital patients, and other vulnerable groups throughout much of the 20th century. A significant shift in medical ethics emerged in the early 1970s in response to public outrage over the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where the U.S. government allowed Black males to go untreated for syphilis to observe the disease’s progression. Kligman maintained a defense of his research until his passing in 2010.

Kligman is recognized as the first dermatologist to establish a connection between sun exposure and skin aging. Notably, he patented Retin-A, a vitamin A derivative used to treat acne, in 1967 and obtained a second patent in 1986 after discovering its effectiveness in reducing wrinkles.

Rice remarked, “Retin-A was discovered and made at Holmesburg Prison. They made millions and millions of dollars off the skin on our backs.” Kligman once expressed his enthusiasm about working at Holmesburg: “All I saw before me were acres of skin,” he remarked in a 1966 interview.

Hornblum drew comparisons to the case of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cells were taken without consent in 1951, leading to a significant legal settlement last year with a biomedical company that produced these cells, known as HeLa cells, which became crucial in modern medical research.

After spending around three years in prison for burglary, Rice managed to earn his GED and built a 30-year career in the city’s recreation department, eventually reaching a supervisory role. Meanwhile, he faced multiple admissions to psychiatric hospitals, witnessed the decline of his marriage, and experienced estrangement from his children at times. As he approaches his 80th birthday, he continues to rely on lithium and struggles with sleep issues that require medication.

While Rice is open to accepting reparations, he believes that no sum can truly remedy the harm inflicted upon him and his family. “No amount of money can replace what was done to me, what was done to my children and wife. This thing was generational,” he commented. He concluded, “There’s nothing that can be done to make it right. I’m going to be like this the rest of my life.”