The course that greeted Cyril Walker a century ago for the U.S. Open was a beast, the longest yet in the history of the national championship, and upon seeing it, the diminutive Englishman predicted that the winner would be “a big fellow with the physical strength to stand the strain.”

It turned out to be a man so slight a stiff breeze seemed as if it would blow him over.

Over four rounds played across two brutal days at Oakland Hills, just outside of Detroit, the unsung Walker bested defending champion Bobby Jones along with some of golf’s greatest players. It was the pinnacle of his career, if not his life, because what followed was a downward spiral fueled by anger and alcohol. It ended in a New Jersey jail cell, where the penniless former pro had sought refuge from the rain and cold, only to be found the next morning dead of pneumonia.

As the U.S. Open prepares to get underway Thursday at Pinehurst, the historic Donald Ross design that famously crowned Payne Stewart its champion 25 years ago, it may be worth remembering the curious story of a most unexpected champion.

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Walker was born in Manchester, England, in 1892, and the few records left describe a typical youngster: He was drawn to cricket and soccer, and he played both well. How he found golf was by sheer happenstance: One day, the 11-year-old wandered through a gate looking for a lost soccer ball and found himself on the grounds of Clayton Golf Club.

He began caddying for sixpence a round and used the money to buy some clubs, and soon was among the best players around.

After leaving school, Walker began clerking at a brokerage firm. But against his father’s wishes, he decided to become a golf pro, back when it was hardly glitz and glamor. He spent his days at Hoylake repairing golf clubs before emigrating to the U.S., where a letter of recommendation from U.S. Amateur champion Jerry Travers helped him land his first job.

Walker found the pace of life so stressful that it would affect him the rest of his days: “The American custom to hurry was my undoing,” he wrote. “Crowded days undermined my health. In time, I developed chronic intestinal inflammation.”

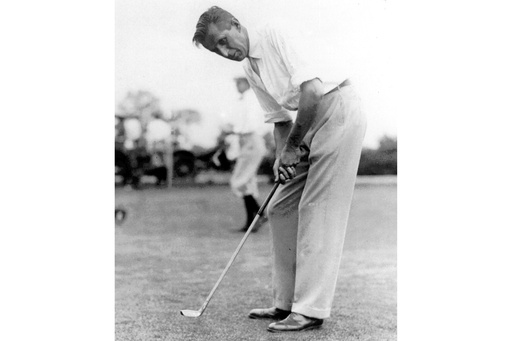

To say that Walker was slight would be a trivialization; he was 5-foot-6 and 118 pounds. But the famed sports writer Grantland Rice described his swing as if he was “cracking a whip,” and that allowed Walker to keep up with much stronger players. He won the Indiana Open and Pennsylvania Open, and in 1921, finished 13th in the U.S. Open and made the semifinals of the PGA — at the time match play competition — that was won by the great Walter Hagen.

HIS DAY IN THE SUN

Walker wasn’t even sure he was going to play the U.S. Open in 1924. He was on vacation in Michigan and decided, almost on a lark, to enter the tournament. He had been playing well and was feeling confident, telling his soon-to-be-estranged wife Elizabeth that he would win, despite saying publicly, “It’s too much for me. The course is too big.”

Walker opened with back-to-back 74s on the first day, leaving him two shots back of William Melhorn and Jones, widely considered the greatest player of his era and the future co-founder of Augusta National.

The second day brought whipping wind to Oakland Hills, making the 6,688-yard course play even longer. But it was perfect for the low, stinging shot Walker had honed playing along the Lancashire coast. He shot another 74 in the third round, leaving him a shot behind Jones — playing in a group 20 minutes of ahead of him — entering the final round later that day.

The decisive moment came at the par-4 16th hole. Walker’s playing partner, Leo Diegel, had just hit into the pond short of the green. Walker changed clubs three times, marched off the distance — 190 yards — at least that many, then hit his approach to 8 feet and made birdie. Tommy Armour, a three-time major winner, would call it “the finest shot I’ve ever seen.”

Walker went on to win by three, hoisting the Wanamaker Trophy, which would later be held aloft by the likes of Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer and Tiger Woods. Jones was typically gracious in defeat, saying that “any man who can shoot that last nine in par today deserves to be the champion.”

HIGHEST HIGHS, LOWEST LOWS

Walker earned a gold medal and $500 for the triumph, but he would make much more money. He played lucrative exhibitions with Bobby Cruickshank, endorsed “Correct Golf Grips” and wrote a syndicated newspaper column that offered advice, even though he loathed fans for being noisy and distracting.

Most disliked the combustible Walker in return. He played so slow he was described as “a cross between a caterpillar and ‘Jersey Lightning,’” a distilled hard cider with a high alcohol content. Soon, fellow pros flatly refused to play with him.

The tipping point came at the Los Angeles Open in 1929, when officials warned Walker to speed up. He replied, “I’m a U.S. Open champion and I’ve come 5,000 miles to play in your diddly-bump tournament, and I’ll play as slow as I damn well please.” Three holes later, he was disqualified. Told of the ruling, Walker replied: “The hell I am. I came to play and I’m going to play.” Two police officers thought otherwise, physically carrying him off the course.

That fall, the stock market crashed, and Walker lost almost everything. He played sporadically over the years, even playing in the first Masters in 1934, where he never broke 80 and finished last. He slipped into irrelevance.

IGNOMINIOUS ENDING

By the time a reporter found Walker years later, the fortune of about $150,000 that he amassed after the U.S. Open — about $2.75 million these days — was gone. Walker was caddying in Miami, where a man who once dressed smartly in a vest and linen plus-fours was wearing the same ratty turtleneck every day because it was the only shirt he owned.

On good days, Walker paid 25 cents to stay in a Salvation Army home. On bad days, he slept on a park bench.

Walker eventually moved back north, to Hackensack, New Jersey, close to where he once served as the club pro at Englewood Country Club. He spent his last years trying to make ends meet as a dishwasher at a diner. Whatever money was left over after paying for room and board at the local YMCA was often squandered on alcohol.

So it came to be that on a rainy night in 1948, Walker walked into a Hackensack police station. He asked the sergeant, Ralph Pinot, if he could sleep in a jail cell to escape the cold. He still had a slightly crooked smile, and in the rare moments it surfaced, his left eye still seemed to close as if he was winking, but otherwise little was left of the U.S. Open champion.

The next morning, officers found Walker slumped over on a chair. The official cause of death was pneumonia, and he was buried in a potter’s field, where no gravestone was left to mark his body. He was 55 years old.

“Self-confidence is a great thing. It is absolutely necessary to believe in yourself in order to accomplish anything,” Walker had written earlier in life, advice he evidently forgot along the way. “This is old stuff, perhaps, but it applies especially in golf.”

___

AP golf: https://apnews.com/hub/golf