Scientists are making strides in understanding the factors that trigger Huntington’s disease, a cruel and hereditary condition that primarily affects individuals in the prime of their lives. This disorder leads to the degeneration and eventual death of nerve cells in specific brain regions, bringing about severe consequences.

While the genetic mutation responsible for Huntington’s disease has been identified for some time, researchers were puzzled by the phenomenon that individuals could possess this mutation from birth yet show no symptoms until later in life. New findings reveal that the initial mutation remains benign for many years. However, it ultimately escalates into a more significant mutation that generates harmful proteins, leading to the death of the affected cells.

Dr. Mark Mehler, who heads the Institute for Brain Disorders and Neural Regeneration at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, emphasized the importance of this new research, highlighting it as a “landmark” study that addresses long-standing questions in the field of Huntington’s disease. Symptoms typically emerge between the ages of 30 and 50 and include impaired motor functions, cognitive decline, changes in personality, and compromised judgment. These symptoms gradually worsen over a period that can last from 10 to 25 years.

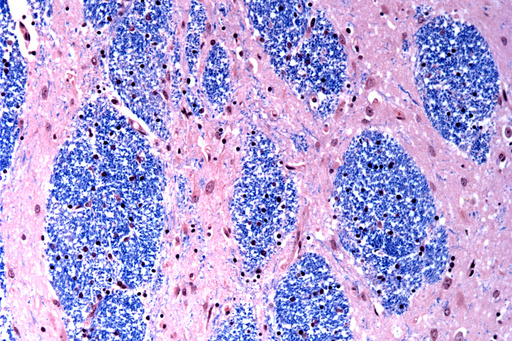

Researchers from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, McLean Hospital, and Harvard Medical School conducted an extensive analysis of brain tissue from 53 Huntington’s patients and 50 healthy individuals, examining approximately half a million cells. Their primary focus was on a specific mutation within the Huntington’s gene characterized by a repeating sequence of three nucleotides (CAG) that appears at least 40 times. In individuals without the disease, this CAG sequence typically repeats between 15 to 35 times. Their research found that these DNA sequences with 40 or more repeats expand over time, eventually exceeding hundreds of CAGs. Once they surpass a critical threshold of around 150 CAGs, certain brain cells begin to deteriorate and die.

The results of the study were unexpected even for the researchers involved, according to Steve McCarroll, a member of the Broad Institute and co-senior author of the report, which was recently published in the journal Cell. The research team observed that the expansion of the DNA repeats occurs slowly during the first two decades of life, with a notable acceleration occurring once the count reaches approximately 80 CAGs.

Neuroscience researcher Sabina Berretta, also a senior author of the study, noted that longer repeat sequences correlate with an earlier onset of the disease. Some in the scientific community expressed skepticism about these findings at conferences, particularly as earlier research suggested that expansions between 30 to 100 CAGs were necessary but insufficient to initiate Huntington’s disease. McCarroll acknowledged that while sequences with fewer than 100 CAGs may not trigger the disease, those with at least 150 CAGs certainly do.

The research team is optimistic that these insights may lead to new strategies for delaying or potentially preventing this currently incurable condition, which affects approximately 41,000 individuals in the United States. Currently, treatment options are limited to medications aimed at managing the symptoms.

Recent trials of experimental drugs intended to decrease the levels of the toxic protein associated with the mutated Huntington’s gene have faced challenges. According to the researchers, the findings suggest that these difficulties may stem from the fact that only a small number of cells harbor the harmful protein at any given moment. Therefore, focusing on halting or slowing the expansion of these DNA repeats might provide a more effective approach to addressing the disease.

Although it is uncertain whether this strategy could definitively prevent Huntington’s disease, McCarroll indicated that several companies are initiating or expanding their efforts to pursue this promising avenue of research.