TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Nestled within Florida’s pristine golf courses and expansive neighborhoods lies the lingering evidence of its slave-holding past: neglected cemeteries for enslaved individuals, statues commemorating Confederate soldiers overlooking town squares, and historical plantations that have transitioned into contemporary housing developments yet retain their original names. However, many students in Florida schools are not exposed to this critical aspect of Black history.

In an antique wooden bungalow located in Delray Beach, Charlene Farrington and her team convene groups of teenagers on Saturday mornings to impart lessons about their heritage, which they worry public schools fail to provide adequately. Discussions include South Florida’s Caribbean heritage, the state’s grim history with lynchings, the lasting impact of segregation, and the grassroots activism that propelled the Civil Rights Movement, seeking to dismantle decades of oppression.

“You need to know how it happened before so you can decide how you want it to happen again,” she expressed to her students, who were seated at their desks, with historic photographs brightening the walls around them.

Students throughout the state are dedicating their Saturday mornings to explore African American history through programs at institutions such as the Spady Cultural Heritage Museum in Delray Beach, as well as similar initiatives at community centers. These programs often receive support from Black churches, which have significantly contributed to shaping the cultural and political identities of their congregants over the years.

Since the launch of its Black history toolkit last year by Faith in Florida, over 400 congregations have committed to delivering these lessons, according to the advocacy group. Florida has mandated the teaching of African American history in public schools for 30 years, but trust in the state’s education system to thoroughly address the topic has diminished among many families.

According to the state’s own evaluations, only a small handful of Florida school districts—just 12—have shown exceptional efforts in teaching Black history, which entails providing evidence of integrating the content into lessons year-round and securing support from school boards and community partners.

School district administrators across the state reiterated their compliance with the government mandate to educate students on the impacts of slavery, the abolitionist movement, and the essential contributions of African Americans to the fabric of American society. Nonetheless, students and parents commonly critique the instruction as being confined to iconic figures like Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, with little extension beyond the annual observance of Black History Month each February.

Sulaya Williams faced challenges in finding comprehensive Black history education for her child when he began school. In response, she established her own organization in 2016 aimed at providing Black history teachings in community venues. “We wanted to ensure our children knew our stories so they could ultimately pass them down to their children,” Williams reflected.

Williams has since secured a contract to offer Saturday classes at a public library in Fort Lauderdale, where her 12-year-old daughter, Addah Gordon, encourages her classmates to participate. “It feels like I’m really learning my culture. Like I’m learning what my ancestors did,” Addah shared. “And most people don’t know what they did.”

The requirement for African American history classes emerged amidst a movement towards acknowledging injustices. In 1994, Florida lawmakers unanimously passed the legislation at a time when the state was grappling with its historical transgressions. Historians had recently released an official report detailing the horrific 1923 attack on Rosewood, a predominantly Black community that was destroyed by a white mob. Following the state legislature’s decision to compensate survivors and their descendants, it was regarded as a landmark model for reparations efforts.

“There was a moment of enlightenment in Florida decades ago, genuinely,” commented Marvin Dunn, an author focused on the history of Black Floridians. “However, that enlightenment was short-lived.” Three decades hence, the quality and consistency of African American history instruction remain inadequate in many Florida classrooms, according to various advocates, and have come under scrutiny from Republican Governor Ron DeSantis. He has been a vocal proponent of initiatives to restrict how race and history are addressed in public school curricula.

DeSantis has rallied support against what he terms “wokeness” in education, drawing the attention of conservatives across the nation, including President-elect Donald Trump. Last year, he enacted a law limiting certain race-based discussions within educational institutions and private enterprises, barring teaching that assigns guilt or responsibility for past actions to members of any ethnic group.

Furthermore, his administration blocked the implementation of a new Advanced Placement course focusing on African American Studies, asserting it contravened state legislation and contained historical inaccuracies. A spokesperson from the College Board confirmed that it is unaware of any public schools in Florida currently conducting the African American Studies course, as it is not included in the state’s existing course offerings.

“Individuals interested in promoting the history of the African diaspora can no longer depend solely on schools,” asserted Tameka Bradley Hobbs, manager of Broward County’s African-American Research Library and Cultural Center. “It’s become increasingly evident that we must foster self-reliance and self-determination when it comes to preserving our history and heritage.”

Currently, only 30 out of Florida’s 67 traditional school districts offer at least one dedicated course on African American history, based on state data from last year. Though not legally mandated, the presence of a separate Black history course serves as an indication of how effectively districts are adhering to the state requirement.

Larger urban districts tend to provide these courses more readily than smaller rural counterparts that may enroll fewer than 2,000 students. Even within districts that have designated staff for teaching Black history, some educators harbor concerns about violating state laws, as reported by Brian Knowles, who manages African American, Holocaust, and Latino studies in Palm Beach County.

“There’s a multitude of districts and countless students we are neglecting because we are treading carefully around what is fundamentally American history,” Knowles lamented.

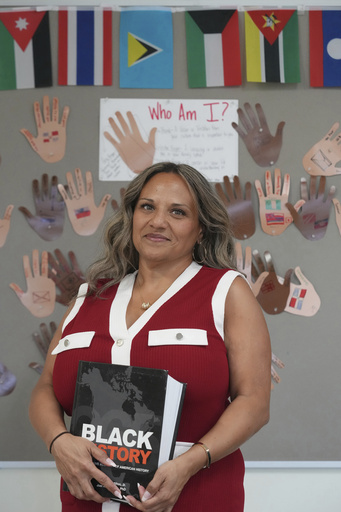

Renee O’Connor, a Black history teacher at Miami Norland Senior High School—which is located in the majority-Black community of Miami Gardens—took a break last year due to frustrations with the limitations imposed on educators. Now back in her classroom, she is actively collaborating with community organizations to devise Black history programs outside of the traditional school environment. “Naturally, I’d prefer that all students could take an African American history class,” O’Connor expressed, “but we must pivot whenever schools fall short.”