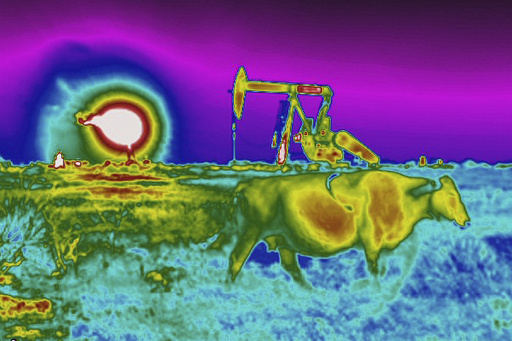

The satellite image reveals a vivid display of colors, and with a digital enhancement, attention is drawn to a prominent red mark indicating the origin: a concrete oil pad that is releasing methane. In the expansive Permian Basin, which spans 75,000 square miles across Texas and New Mexico, significant amounts of this potent greenhouse gas escape from various sources, including wells and compressor stations.

Most initiatives aimed at curbing emissions have zeroed in on “super emitters,” which are relatively straightforward to detect due to advancements in satellite imaging technology and aerial monitoring. However, recent studies indicate that much smaller leak sources contribute to approximately 72% of methane emissions in oil and gas fields throughout the continental U.S. These smaller emitters often remain unnoticed.

James Williams, a post-doctoral science fellow with the Environmental Defense Fund and lead author of a recent extensive study on emissions from the country’s oil and gas regions, emphasized the significance of addressing both high-emitting super emitters and smaller sources. Tackling methane emissions is crucial because it accounts for around one-third of greenhouse gas emissions contributing to global warming.

Experts highlight the difficulty of managing methane emissions in the Permian Basin, home to more than 130,000 active well sites, which vary from family-run operations to major international companies. Each site often hosts numerous oil wells. Steve Hamburg, the chief scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, described the Permian as a complex basin filled with diverse operators and a high density of operations.

Moreover, the infrastructure, including pipelines and processing facilities, can have multiple owners, leading to thousands of locations where methane could leak, whether through unintentional faults or purposeful venting.

In a recent investigation, an Israeli firm utilized satellite data and artificial intelligence to examine leaks in Midland County, Texas, identifying 50 different emission plumes from 16 out of 30 monitored sites. These findings indicated that many sites were emitting over 4,500 kilograms of harmful methane gas every hour, with five sites surpassing 10,000 kilograms — significantly exceeding the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) threshold for super emitters, which is set at 100 kg/h.

Omer Shenhar, a vice president at Momentick, expressed astonishment at the numerous small emissions detected in such a crowded area, particularly close to residential zones. Methane is an alarming greenhouse gas, trapping more than 80 times the heat compared to carbon dioxide and exhibiting a concerning increase in concentration since the pre-industrial era.

The recent launch of a sophisticated satellite named MethaneSAT enables researchers to detect smaller emission sources across vast regions that were previously untraceable to other satellites. According to Hamburg, the ability to track methane over time in key oil-producing areas represents a significant advancement in emissions monitoring.

While the satellite may not be able to pinpoint smaller leak sources, on-ground operators have the means to identify them, Hamburg noted. In the United States, new EPA regulations will soon require oil and gas companies to regularly monitor for leaks at both new and existing sites, including wells and production facilities. This regulation also puts an end to the common practice of venting excess methane — known as flaring — and mandates the upgrading of leaky equipment.

Additionally, states have until 2026 to enact plans for managing existing leak sources under the new rules. Furthermore, oil and gas companies will face federal fees for leaking methane beyond specified limits, though the incoming administration could alter or nullify these regulations.

Methane is the principal component of natural gas, presenting commercial value; however, many operators within the Permian see it as a bothersome byproduct of oil extraction, frequently flaring it due to the lack of pipeline infrastructure to transport it effectively, according to comments from experts Duren and Hamburg. Neither the Permian Basin Petroleum Association nor the U.S. Oil & Gas Association responded to inquiries for statements.

Riley Duren, CEO of the nonprofit Carbon Mapper and not involved in the aforementioned study, emphasized the importance of focusing on super emitters due to their disproportionately high impact, despite the fact that some may only present short-lived emission events.

Ultimately, Duren noted that rather than fixating on the proportions of emissions from large emitters versus numerous small sources, the real challenge lies in determining actionable responses to the gathered information. Given the multitude of equipment involved, opportunities for leaks exist at virtually every turn.