A little over a decade ago, the Oscar-winning actor Al Pacino was living in Beverley Hills and discovered he was broke. “I had $50m and then I had nothing.” Pacino, who had grown up poor in the South Bronx, New York, and struggled to keep his finances in order his whole career, suddenly found he was paying for 16 cars even though he had just two, and 23 mobile phones he didn’t know about. “There’s almost nothing worse for a famous person – there’s being dead, and then there’s being broke.” It turned out he had a crooked accountant as well as a poor eye for figures, but what did Pacino do? He went back to work, of course.

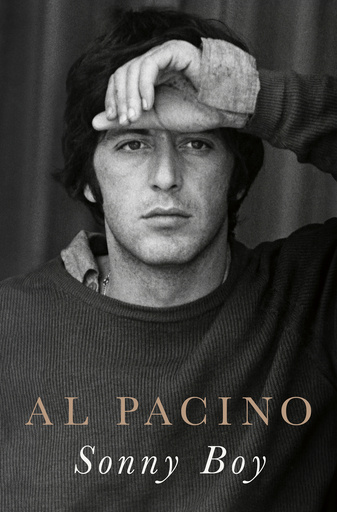

As for why a superstar actor with a reputation for being intensely private might write a memoir, in the case of 84-year-old Al Pacino’s Sonny Boy, the answer could be for the money. Pacino is refreshingly honest about his attitude to the thing most stars are cagey about.

Despite his difficult childhood – his Italian-American parents were teenagers when he was born, both died young, but not before his mum attempted suicide, and three of Pacino’s best childhood friends died of drug overdoses – he never set out to make money. “It was a language I didn’t speak.”

But coming from the background he did, Pacino was also a hard worker. In his youth he had been a bicycle messenger, a house-mover, a cinema usher. He was also wildly literary, despite leaving school early, becoming obsessed with Chekhov after seeing The Seagull on stage as a young adult.

He took to carrying playwrights’ books around thereafter, and used to read obsessively in the library, where he went to stay warm before the fame and the money come along. Throughout the book he casually quotes Molière, Brecht, Shakespeare. He is a passionate scholar, minus the education.

Although the memoir is occasionally frustratingly evasive (he irritably shrugs off the Method acting he became known for; we might guess the bad-mannered Noughties superstar producer who remains nameless), it is good at giving us a sense of Pacino’s voice, flipflopping between the type of self-assuredness that lent itself to endlessly falling out with directors (“See a pattern here?” he notes wryly) – and at the same time struggling with attention

Pacino was entirely unbothered by fame, loathed it even. As his star rose, he developed anxiety, panic attacks, and a drinking problem.

He gained a reputation for being aloof after he failed to attend the Oscars following his first nomination for Best Supporting Actor in 1973 (for The Godfather), but the man that emerges from the pages is more painfully shy. “The world wouldn’t let me be shy,” he laments.

There are meaty anecdotes about stars – annoying Philip Roth, flat-sharing with Martin Sheen, watching Marlon Brando eating chicken cacciatore with his hands (“gobble gobble gobble”), getting together with Diane Keaton, inexplicably holding out his hand like a Roman emperor for Jackie O to kiss one night after performing Richard III. But there are also lengthy passages devoted to just how a film came about and how it was financed, or which particular aspect of it Pacino didn’t approve of. This is really a book for avid film fans, not so much for the general public.

The section likely to please all readers, though, is his trial by fire on The Godfather. Paramount didn’t want him for the part of college graduate turned gangster Michael Corleone, and he nearly lost it while filming. “By the end of the film I hoped that I would have created an enigma,” he says carefully about his now iconic performance, but he knew at the start it wasn’t quite cutting it.

Perhaps another motivation for the book was legacy. After a lifetime spent living stubbornly in the present, he is all reflection and nostalgia as the book comes to a close, particularly following a near-death experience with Covid when he briefly had no pulse. “I returned and I can tell you there’s nothing there. It’s over.”

Although the memoir ends with memories of family and friends, it’s clear it’s his films he wants most to be remembered by. This is a book less about a man than an actor through and through. As he writes here, he was asked in an interview once what he thought God would say at the pearly gates. Pacino replied: “I hope He says rehearsal starts tomorrow at 3pm.”