WASHINGTON — The discovery of an ancient, colossal arthropod—reaching lengths of nearly 9 feet and weighing over 100 pounds—has sparked curiosity about its appearance, particularly its head. Most fossils unearthed from this species are headless, preserved exoskeletons representative of a molting process, wherein these gigantic creatures shed their exoskeletons to accommodate their growth.

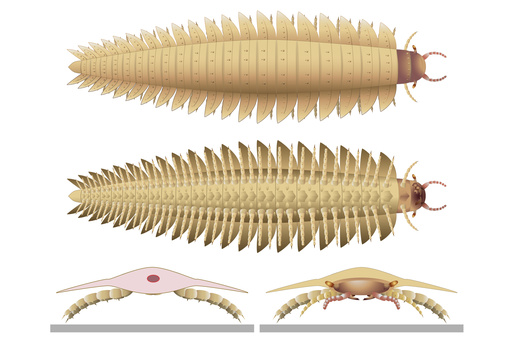

Recent research offers new insights as scientists examined remarkably preserved juvenile fossils that provided a clearer picture of the creature’s head. The findings reveal that this giant insect, named Arthropleura, boasted a rounded head with two short, bell-shaped antennae, crab-like protruding eyes, and a small mouth adapted for grinding foliage and bark. This recent research, published in the journal Science Advances, has opened up discussions surrounding the appearance of these fascinating creatures.

Arthropleura is categorized within the arthropod family, which includes modern insects, spiders, and crabs. Despite their intimidating size, these ancient organisms share characteristics with today’s millipedes and centipedes, showcasing an unexpected blend of features. According to Mickael Lheritier, a co-author of the study and a paleobiologist from the University Claude Bernard Lyon, “We discovered that it had the body of a millipede, but head of a centipede.”

There’s ongoing debate concerning whether Arthropleura was the largest insect to roam the Earth, as some suggest it could be rivaled closely by an extinct giant sea scorpion. Scientists across Europe and North America have been gathering fossils and footprints of these massive arthropods since the late 19th century, fueling efforts to reconstruct their appearance over the years.

James Lamsdell, a paleobiologist at West Virginia University who did not participate in the study, expressed excitement about the findings: “We have been wanting to see what the head of this animal looked like for a really long time.” The process of reconstructing the head model involved using CT scans to examine fully intact juvenile fossils found embedded in rocks within a French coal field back in the 1980s.

This advanced methodology allowed researchers to explore intricate details, including portions of the head that remained encased within the rock, without damaging the fossils. Lamsdell emphasized the importance of this technique, stating, “When you chip away at rock, you don’t know what part of a delicate fossil may have been lost or damaged.”

The juvenile fossils observed were approximately 2 inches (6 centimeters) long, suggesting they may represent a smaller variant of Arthropleura that did not reach titanic proportions. However, the researchers believe these remains offer crucial insights into the overall appearance of their larger counterparts that roamed the Earth 300 million years ago—whether they were of a more manageable size or heighted nightmares.