SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — Dozens of South Korean adoptees, many in tears, have responded to an investigation led by The Associated Press and documented by Frontline (PBS) last week on Korean adoptions. The investigation reported dubious child-gathering practices and fraudulent paperwork involving South Korea’s foreign adoption program, which peaked in the 1970s and `80s amid huge Western demands for babies.

Here are some of the problems adoptees who responded say they faced, along with tips for finding histories and birth families.

KYLA POSTREL — Adoption paperwork tells multiple stories

Kyla Postrel’s paperwork tells two different stories, neither of which she’s sure is true.

After a DNA test last year, Postrel found a half-brother who was also adopted to the West. Comparing their paperwork made her even more skeptical of the stories they’d been told. But part of her is reluctant to keep looking “for something that may or may not exist and could be absolutely devastating.”

She has been flooded with messages from other adoptees looking for help, and tells them not to be disappointed if they can’t track down their stories.

“I just don’t want any adoptees feeling like their life is a lie,” she says. “Their life is everything that they’ve built since then.”

If her birth mother is still out there, Postrel would want her to know her daughter has had a good life.

CODY DUET — Not enough information in the file

Cody Duet, adopted to rural Louisiana in 1986, requested his full file a decade ago. He got back less than one page, saying his mother was a young factory worker, his father was unknown and there was nothing more they were required to give him.

“It was probably one of the most angry moments in my life,” Duet says. “Who are you to tell me that I don’t get to know who I am?”

He fell into a depression and couldn’t sleep. He struggled with abandonment, like he was easy to get rid of, easy not to love. But now, he wonders, was that story even true?

The AP investigation found that children were systemically listed as abandoned, even though researchers have found that the vast majority had known relatives.

Now Duet wants to resume his search. He wants to find his mother, to tell her he’s reached a point in his life that he’s proud of.

AMY McFADDEN — Some adoptees don’t know what to believe

Amy McFadden always believed what the adoption agency told her parents — that she was abandoned on a staircase at 5 weeks old.

Adopted to the United States in 1975, she’d heard stories about fraudulent adoptions, but always thought of them as one-off problems that had nothing to do with her. She’s grateful for her American life and close to her adoptive parents, and never felt the longing so many other adoptees do to reconnect with their roots.

But when she found out from the AP stories that mothers in South Korea have searched for their missing children for decades, she says, she was in shock for three days. Waves of nausea radiated over her.

She wants to submit her DNA, in case a family has been looking for her.

CALLIE CHAMBERLAIN — Not everyone has a happy ending

For Callie Chamberlain, waiting for word on whether her birth parents wanted to connect felt like standing on the edge of a cliff.

Her original documents said her mother was young, unmarried and uneducated, she says. Her full files from the South Korean agency contained a different story: Her mother was married and she was born of an affair. DNA testing showed both stories were untrue, and identified her mother and father as married both back then and now.

When they connected, her mother said she’d nearly died giving birth. The family was poor. Disoriented from labor and medications, her mother said she only vaguely remembered hospital staff insisting she was very sick and the child deserved a better home. The baby disappeared the next day. She lived with that shame for years, and the entire family searched for Chamberlain.

They have now invited her — and her adoptive family — with open arms. But Chamberlain has met many without such happy endings, and feels a sort of survivor’s guilt. She also questions the belief that reunions will answer all questions and make you whole.

“There is so much grief and there’s so much sorrow,” she says. “There’s this sense of death. And then there’s also so much that gets to be born. It’s an ancestral sorrow that I can feel sometimes, like this wasn’t supposed to happen.”

She has learned of a Korean cultural concept called “han,” an existential and endless grief, born from colonization, war, poverty and the line that cleaves Korea into North and South, splitting families for generations. “That’s something we experience too,” she said. “We are Koreans.”

___

Here are some steps Korean adoptees could take to learn more about their past:

Do birth family searches

Adoptees can first request information from their adoption agencies. If they don’t get results from agencies, they can contact the South Korean government’s National Center for the Rights of the Child as a second step.

Birth searches can take months and aren’t always successful. Less than a fifth of 15,000 adoptees who have asked the government for help with family searches since 2012 have managed to reunite with relatives, according to data obtained by AP. Failures are often caused by inaccurate records or the practice of describing children as abandoned even when they had known parents.

Many adoptees also criticize the consent process for reunions. Adoption agencies and the NCRC can only use traditional mail, and only up to three times per search, to contact birth parents for their consent to provide personal details to adoptees and meet them. Privacy laws prevent agency and NCRC workers from accessing birth parents’ phone numbers. Still, the Korean-language adoption documents kept by South Korean agencies often have more background information than translated files sent to Western adoptive parents. When they don’t get results, adoptees can request another search after a year.

When they fail to locate birth parents, NCRC may recommend that adoptees register their DNA with South Korean police or diplomatic offices, or help them publish their stories in South Korean media.

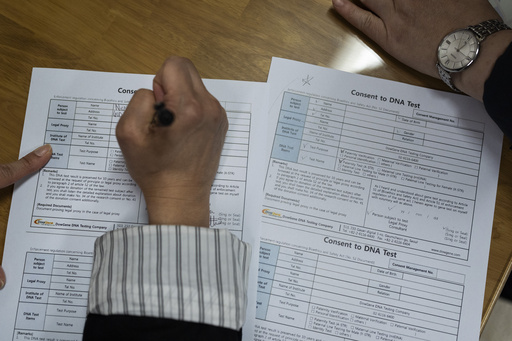

Take a DNA test

Frustrated with search failures and unreliable records, many Korean adoptees in recent years have attempted to reconnect with their birth families through DNA. Adoptees can register their DNA with a South Korean embassy or consulate in the country where they live. They can also register their DNA with a local police station if they travel to South Korea.

DNA testing isn’t common in South Korea, and the process usually depends on whether the birth family had also been trying to find the adoptee through DNA. Once collected at diplomatic or police offices, adoptees’ genetic information is cross-checked with South Korea’s national DNA database for missing persons. When there is a match, the NCRC takes steps to arrange a reunion.

Some adoptees have also found birth relatives through commercial DNA tests popular in the West. The nonprofit group 325 Kamra helps South Korean adoptees and birth families reunite through DNA, by allowing adoptees to upload their commercial test results to a database or providing test kits.

Join adoptee and volunteer groups

There are various Facebook groups — some open, others closed for adoptees only — where adoptees talk about their lives and interactions with adoption agencies.

One of the most active pages is run by Banet, a volunteer group named after the Korean word for newborn baby clothing. The group helps adoptees search for birth families, connects them with government and police, and provides translation during meetings with Korean relatives.

Some websites are tailored to adoptees sharing the same agency, such as Paperslip, which helps adoptees placed through Korea Social Service with birth family searches and adoption document requests.

The Seoul-based nonprofit Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link assists adoptees with birth family searches as well as language education, social events and obtaining visas for employment in South Korea. KoRoot, another Seoul-based civic group, also helps adoptees searching for their families and backgrounds and runs advocacy programs.

—-

This story is part of an ongoing investigation led by The Associated Press in collaboration with FRONTLINE (PBS). The investigation includes an interactive and documentary, South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning. Contact AP’s global investigative team at [email protected].