Key Point Summary – Toxic Tacoma Killers

- Three notorious serial killers lived near Tacoma in 1961

- Scientists now link lead and arsenic exposure to violence

- Tacoma’s ASARCO smelter spewed deadly pollutants for decades

- Lead and arsenic may have altered developing brains

- New book ties pollution to rise in U.S. serial killers

- Other cities near smelters saw similar patterns

- Even UK killers shared the same toxic exposure history

A Storm. A Missing Child. A Future Killer?

In the early hours of August 31, 1961, a thunderstorm rattled the quiet city of Tacoma, Washington. Amid the downpour, 8-year-old Ann Burr vanished from her home. Her small footprint was found near a window. But the case went cold.

Authorities never made an arrest. Yet many now believe Ann was the first victim of Ted Bundy—just 14 at the time and living nearby. A boy delivering newspapers. A monster in the making.

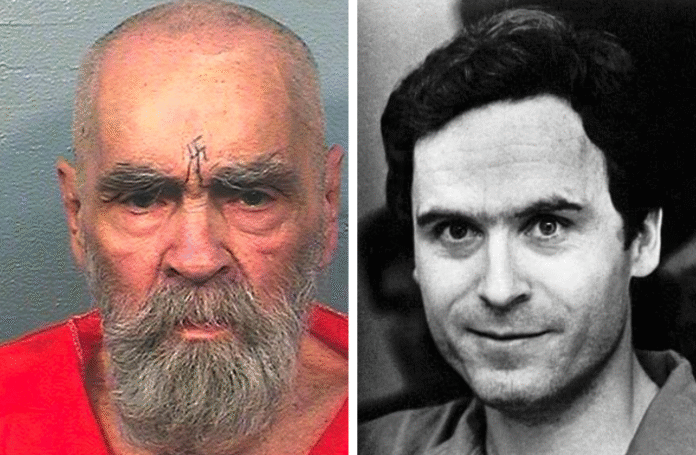

Bundy would become one of America’s most chilling serial killers. But he wasn’t alone. That same year, two other future killers lurked nearby.

Three Monsters, One Neighborhood

Charles Manson, 26, sat behind bars on McNeil Island—just ten miles away. He would later lead the Manson Family cult in a spree of murders that stunned the nation.

Twelve-year-old Gary Ridgway also called the Tacoma area home. He would grow into the Green River Killer, strangling dozens of women and committing acts of necrophilia.

It sounds like fiction. But it’s not. And now, researchers say there’s a terrifying reason why these monsters emerged from one place.

Toxic Tacoma Killers: A Deadly Link?

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Caroline Fraser believes it wasn’t just coincidence. Her new book, Murderland, argues that environmental toxins may have helped create serial killers.

At the center of the theory: Tacoma’s towering 562-foot smokestack. The ASARCO copper smelter.

For nearly a century, the plant belched out clouds of lead and arsenic. These invisible poisons rained down on neighborhoods, blanketing soil, coating cars, and contaminating air and water.

The area’s residents knew it was bad. But they didn’t know how bad.

Poison in the Playground

The plant pumped out more sulfur dioxide than Mount St. Helens. In heavy rains, acid rain destroyed gardens. ASARCO sent staff door-to-door with cash payouts.

Workers developed a grotesque condition dubbed “smelter nose”—where nasal passages eroded from prolonged fume exposure.

Children played in yards tainted with toxic ash. Local blood tests revealed sky-high lead levels. But it wasn’t until 1986 that the plant finally shut down.

By then, the damage was done.

Lead, Arsenic, and the Brain

Scientists have long linked lead exposure to violent behavior. Children absorb lead easily. It disrupts brain development. It impairs impulse control and increases aggression.

Arsenic, another smelter byproduct, causes cognitive dysfunction and memory loss. Combined, they may help explain the rise of the Toxic Tacoma Killers.

Fraser studied lead levels in areas where Bundy, Ridgway, and Manson lived. The numbers were shocking. So were the murder totals.

A Wave of Blood Across the Northwest

Washington State saw a disturbing concentration of serial killers in the 1970s and 1980s. At least half a dozen were active in the region.

Randall Woodfield, the I-5 Killer, murdered dozens along the highway. Jack Spillman, the Werewolf Butcher, confessed to mutilating his victims. Satanist Israel Keyes preferred strangulation—just like Bundy.

They weren’t outliers. They were part of a grim pattern.

Smog, Slag, and Sociopaths

ASARCO wasn’t just spitting pollution into the air. It was dumping 600 tons of lead-and-arsenic slag into the sea daily—until 1974. That’s when it started selling it as driveway gravel.

It sounds insane. But that gravel ended up outside people’s homes. Kids walked over it. Dogs dug in it. And all the while, the killers grew up nearby.

Serial killers, defined as people who commit at least three separate murders, peaked in the U.S. in the 1970s. The timeline fits.

Fraser believes that Tacoma’s toxic legacy made its mark—not just on bodies, but on minds.

Deadly Patterns Repeat Elsewhere

Tacoma isn’t the only city tied to this gruesome trend. Fraser points to El Paso, Texas. ASARCO ran another smelter there. Three serial killers—including Richard Ramirez, the Night Stalker—grew up near it.

Ramirez committed at least 14 brutal murders in California. His trial exposed levels of evil that still shock.

Others, like John Agrue and David Leonard Wood, were also raised in El Paso. All three had one thing in common: lead exposure.

Murder Maps: Tracing the Toxins

From the Midwest to the Pacific Northwest, Murderland draws lines on the map between serial killers and polluted cities.

The Hillside Stranglers, BTK, and John Wayne Gacy all lived in high-exposure zones. So did Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, and even Harold Shipman, Britain’s deadliest doctor.

Fraser says it’s more than coincidence.

In West Yorkshire, where Sutcliffe roamed, lead mining had gone on for centuries. Factories fouled the air. Children grew up sick and struggling. Some turned violent.

A Forgotten Victim: The City Itself

Tacoma, once called the “aroma of Tacoma” for its foul industrial smell, has cleaned up since ASARCO closed. But scars remain.

The land is still monitored for contamination. Generations were affected. And some believe the city still carries a hidden curse.

Locals recall pets dying young, gardens failing, kids always sick. Now, they wonder: did the city’s pollution not just poison lungs—but minds too?

Public Reaction: Horror, Then Reflection

Fraser’s findings have stunned readers and experts. Some call it speculative. Others say it’s long overdue.

“Ted Bundy wasn’t born a monster,” one commenter wrote online. “Maybe Tacoma helped make him one.”

On social media, many from Tacoma shared childhood memories of the white ash, the acid rain, the nosebleeds.

Some felt guilt. Others felt anger. But most felt a haunting connection between the environment they grew up in—and the evil that once walked among them.

What Comes Next?

The EPA has acknowledged the long-term damage from the Tacoma smelter. Clean-up efforts have continued for decades.

But what of other towns with similar toxic legacies? Will anyone study them? Will governments take accountability?

Fraser hopes her book sparks more than fear. She wants action. Better monitoring. Tougher regulations. And more awareness of what poisons can do—not just to the body, but to the soul.

Because if Toxic Tacoma Killers taught us anything, it’s this: the most terrifying monsters may not be born. They might be made—by the very air we breathe.