CAPE TOWN, South Africa (AP) — South Africa is in a moment of deep soul-searching after an election that brought a jarring split from the African National Congress, the very party that gave it freedom and democracy 30 years ago.

In the days after rejecting what was once the country’s most beloved organization, South Africans were dealing with essential questions over not just where they were going, but what they’d achieved in their young democracy since ending the racist apartheid system of white minority rule in 1994.

Despite having Africa’s most industrialized economy, the injustices of South Africa’s past have not been made right three decades after Nelson Mandela and the ANC were elected in the country’s first all-race vote and promised a better life for all. That has driven discontent among millions of the poor Black majority.

“We remain the pyramid society that apartheid and colonialism created,” said Thuli Madonsela, a professor of law who helped craft a new, post-apartheid constitution for South Africa in 1997 that was meant to guarantee everyone was equal from then on.

Speaking on national broadcaster SABC, Madonsela outlined how South Africa’s democratic journey is still marred by vast problems of joblessness and race-based inequality at some of the worst levels in the world. In last week’s election, opposition parties were united in one thing: Something had to change in the country of 62 million.

The problems are both the hard-to-heal scars of apartheid and the contemporary failings of the ANC. The nation, once a prime example of brutal oppression that then embodied a great hope through Mandela, is still searching for what it wants to be — but self-aware, at least.

“What must we do with this South Africa of ours?” asked Thabo Mbeki, the former South African president who had the almost impossible task of succeeding Mandela as his nation’s leader.

Politically, South Africa is heading into the unknown again as it did after the turning-point election of 1994, but with none of the joy or optimism of a transition celebrated across the world. The ANC has lost its majority, but with no other party overtaking it, South Africa faces what might be an excruciating series of negotiations to form the first national coalition government in its history.

Yet amid the uncertainty and South Africans’ introspection, some have urged them to be proud and to take a closer look at what just happened.

The ANC has accepted the result of the election and the will of the people without question, even after it ended such a long political dominance that it was sometimes hard to see where the ANC ended and South Africa began. An ANC leader once said in bluster that it would govern South Africa “until Jesus comes back,” but it graciously submitted to the will of the people last weekend and pledged to work with opposition parties for the good of the country.

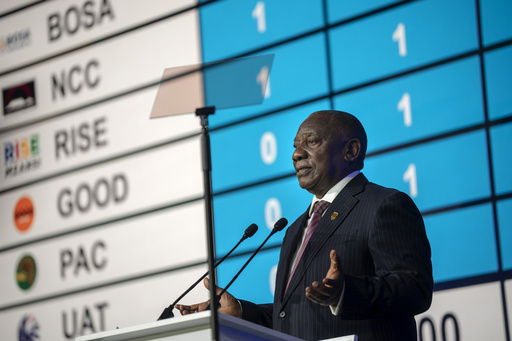

After the election results were officially declared Sunday night, South Africans went to work Monday and their children went to school. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, while still digesting a historic defeat for the party he leads, sent an online message to the nation like he does at the start of every week. He began it with the words: “We have just held a successful general election” and wrote that the vote showed “that our democracy is strong, that it is robust and that it endures.”

Frans Cronje, a political and economic analyst, said that shouldn’t be lost given how other long-ruling post-colonial political parties in Africa have rejected election results and clung to power, sending their countries spiraling. And there have been efforts in recent years to subvert democracy and elections further afield in bigger countries, he said.

“There’s actually not much to see here (in South Africa) other than a democracy that worked in a world where they don’t always work as well as the architects of Western democracy would have wanted them to,” Cronje said. Cronje said it was “the least profound” observation he could make, and yet it might have gone unnoticed.

It wasn’t meant to underestimate South Africa’s troubles, though, and they are stark: The South African Human Rights Commission, one of several independent bodies set up by the government with a mandate to guard democracy, found in 2021 that 64% of Black people in South Africa and 40% of those with biracial heritage were classified as poor, but for white people that figure was only 1%.

That must change quickly, Madonsela warned, or South Africa’s democracy could face sterner tests ahead and the constitution that she co-wrote could be in danger of becoming “meaningless” to people. She cautioned that some might conflate the failure of the ANC with the failure of democracy as a whole. More than 80% of South Africa’s population is Black and the frustration of millions over broken government promises cannot be underestimated.

South Africa’s future now lies in coalition talks that will bring almost every major party in, although it’s still unclear what the final product will be. More than 50 parties contested last week’s election, with at least eight receiving significant shares of the vote, reflecting a country that has never pretended not to be complicated. Ramaphosa said South Africa has to find unity “now more than ever.”

As politically and racially diverse groups try to chart a new way forward together, an optimistic South African might find a connection with one of the most famous speeches Mandela gave 60 years ago when he stood in an apartheid courtroom and held firm in his defense of democracy, and that every South African be allowed to vote and have a say in their future.

“We believe that South Africa belongs to all the people who live in it,” he said.

___

AP Africa news: https://apnews.com/hub/africa

Home World Live World South Africa questions its very being. Yet a difficult change has reinforced...